We are now eight years into the economic recovery in the U.S., arguably the latter stages of a mature expansion and at a point where inflationary pressures typically begin to build. Yet price and wage inflation remain stubbornly subdued.

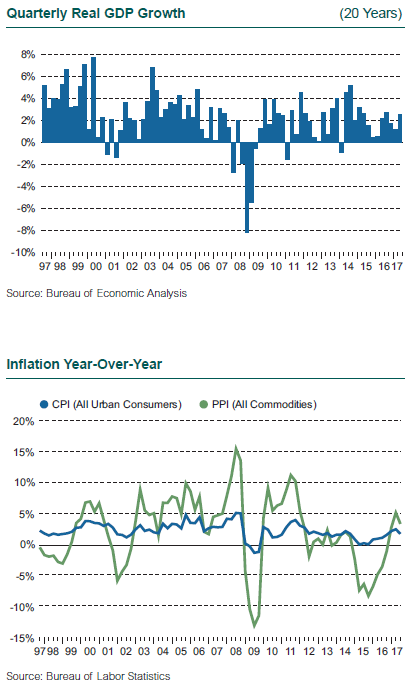

Headline and particularly core inflation have drifted down over the past several months. Headline inflation (the CPI–All Urban) climbed above 2% in December 2016 and stayed near 2.5% until May 2017, when it began to ebb. The Index was unchanged in June, meaning zero inflation month to month; the year-over-year change is now 1.6%. The Fed’s targeted measure of core inflation (personal consumption expenditures (PCE) less food and energy) showed a year-over-year gain of just 1.5% in June. This decline in core inflation is both baffling and frustrating to the Fed, and it provides a headwind to its efforts to bring interest rates back to “normal.”

Low wage growth is also a mystery in the U.S., where it has remained below 3% for years while the unemployment rate has fallen to a 16-year low of 4.4% in June, and stories of tight labor markets abound in industries around the country.

The explanations for persistent low inflation are varied, but there is no consensus on the cause. The most plausible reasons include: 1) lackluster global growth; 2) excess industrial capacity, much of it in China, pushing down goods prices; and 3) technology, specifically product and process innovations that slash production costs.

Weak wage growth is more of a conundrum, especially in economies such as the U.S. that appear to be at full employment. Why hasn’t the job market pressure pushed up overall wages? More plausible explanations include: 1) a large pool of workers not properly captured in the official unemployment data (discouraged workers, the long-term unemployed); 2) the replacement of retiring higher-wage baby boomers with lower-wage young workers, skewing the average wage downward; 3) poor productivity growth, paired with 4) use of technology to replace workers with capital, particularly in low-wage, low-skilled jobs; and 5) a related shift in market power from labor to capital. None of these factors alone explain the persistence of low inflation and low wage growth, but the interaction of these factors tells a believable story.

Why is persistent low inflation a problem? The most commonly cited concern is the potential for weaker inflation to stall the Fed’s efforts to normalize interest rates. Lack of inflation must mean weakening prospects for growth. We believe we know how to tame inflation should it take off, but the prospect of deflation is truly terrifying.

In addition to the conundrum of low inflation, the state of growth weighs heavily on the Fed’s deliberations on the path to future interest rate hikes and the size of its balance sheet. The U.S. economy has ambled on at a reasonable if unspectacular (although sometimes halting) pace for eight years. Second quarter GDP growth came in at 2.6%, roughly in line with expectations. The solid (if unspectacular) figure built on the upward revision to disappointing growth in the first quarter, which was adjusted up from 0.7% to 1.2%. Consumer spending has been the engine for growth, increasing faster than GDP (2.8% in the second quarter), and supported by gains in employment, disposable income, and household wealth. The combination of a strong job market, continued stock market gains, and the expectation for tax cuts coming from the Trump administration and the Republican Congress has fueled consumer confidence, and with it spending, since the start of 2017—although confidence did take a breather in the second quarter.

Business fixed investment enjoyed a strong first quarter with a 7.2% gain, driven by close to 15% growth in structures (including oil and gas mining), and followed with another 5% gain in the second quarter. The rebound in the oil and gas sector suggests the spending on capital has built some momentum.

Residential housing spending took a hit in the second quarter, falling by 6.8%, somewhat in defiance of the laws of economics as the supply of homes for sale is not keeping up with demand. The nation-wide average price for a new home reached an all-time high in May, topping $400,000. High prices should be driving builders to build, but the permits and starts for both single-family and multi-family homes declined in May before recovering somewhat in June. The restraint on construction activity may stem from tightened standards on commercial real estate loans, particularly on multi-family homes, and rising interest rates.

1.6%

Year-over-year change in the CPI–All Urban inflation index in June.