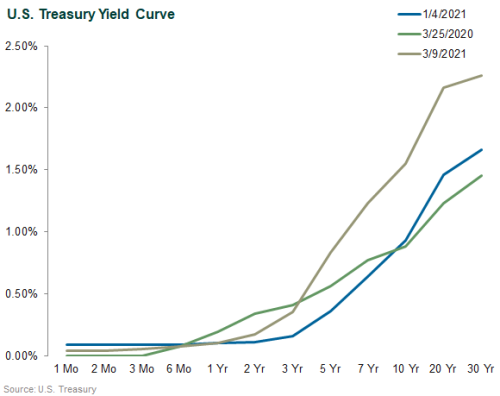

The U.S. Treasury yield curve has steepened dramatically since the start of 2021, with the 10-year yield rising nearly 70 bps while short-term rates remained close to 0%. While still negative, real yields also have risen, by roughly 50 bps since the start of the year. This movement is significant, as the shape of the Treasury yield curve reflects investor expectations for future inflation, which erodes the value of fixed income investments.

The yield curve typically slopes upward, meaning that longer maturity bonds carry higher yields than shorter maturities. Investors demand higher yields as compensation for buying bonds with longer maturities, as these bonds are more exposed to risks such as inflation.

As the pandemic took hold and economies around the world shut down in March 2020, growth and inflation expectations fell sharply, prompting the Federal Reserve to cut short-term rates to effectively zero and enact large-scale asset purchase programs. As a result, yields on short-term U.S. Treasuries have remained close to 0%.

As prospects for growth have brightened on the back of increasing vaccinations, a gradual re-opening across the country, and continued fiscal stimulus, yields on longer maturity bonds have risen while short-term rates have been anchored by the Fed. This shift in the yield curve is known as a “bear steepening,” meaning long-term yields are rising faster than short-term yields. The “bear” reflects the decline in bond prices associated with rising yields. This steepening reflects expectations for higher inflation and is often associated with the beginning of an economic expansion.

What are the ripple effects for institutional investors of rising longer-term yields and higher inflation? Because bond prices fall when yields rise, investors may experience losses in the short-term. However, longer-term, higher yields are beneficial to bond investors, as coupon income is reinvested throughout the life of the bond. And should the U.S. experience a true uptick in inflation, the Federal Reserve would likely tighten monetary policy by raising short-term rates or slowing asset purchases. As the Fed raises rates, companies face higher costs for borrowing, which may reduce earnings and slow capital expenditures, depressing stock prices. Further, rising yields can make stocks less attractive on a relative value basis.

Despite the recent rise in yields and increased inflation prospects, in recent weeks Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell indicated the central bank would keep its easy money policies in place until substantial progress has been made toward its 2% average inflation target. In an effort to achieve this average target, the Fed will tolerate inflation above its target for a period of time to offset periods when inflation is below target, as it has been for nearly the last decade. Such progress has not yet been reflected in economic data, as the change in the PCE price index—the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge—for the 12 months ended January 2021 was 1.5%, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

For investors, the bottom line seems clear: while the Fed is generally optimistic about the direction of the economy, monetary policy is unlikely to change in the near term.