By Kyle Fekete and Mark Kinoshita

As passive investing becomes a larger part of fund sponsors’ portfolios, investors are encouraged to look underneath the hood of their indexing strategies to evaluate securities lending. This has played an integral role in maintaining low fees (or a source of alpha) for index funds, which is especially critical as the investment industry experiences fee compression.

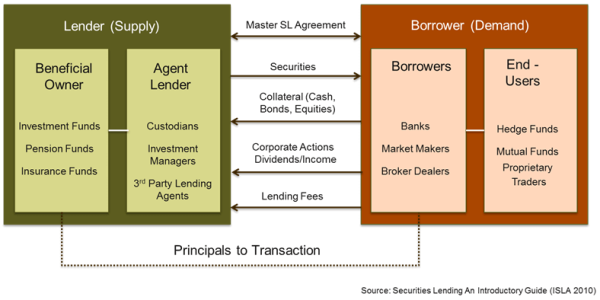

As with any loan, a securities lending transaction involves a lender (in this case a fund sponsor) and a borrower (a market participant or interested counterparty). Fund sponsors participate in direct securities lending through separate accounts, and indirectly through commingled funds such as collective trusts, mutual funds, or ETFs. A lending agent facilitates the transaction by seeking out a borrower and negotiating the loan terms on behalf of the fund sponsor. Borrowers are also represented by a third party, such as a prime broker or a bank, and typically include hedge funds looking to open a short position and other market participants.

Securities lending loan terms are typically left “open” until one of the two parties end the agreement, or made “callable” where the lender has the right to recall the security at any time before the agreed-upon loan term. In exchange for the security, the borrower provides collateral that can come in the form of cash or non-cash. The collateral aims to protect the lender from borrower default and is typically required to be 102%-105% of the value of the borrowed security. On a daily basis, lending agents will mark-to-market to determine if the borrower needs to post additional collateral (“mark-up”) or if the lender must return collateral (“mark-down”) as the value of the borrowed security fluctuates.

The lender or lending agent typically reinvests cash collateral conservatively in very high-quality and highly liquid assets such as U.S. government and agency securities, commercial paper/CDs, and corporate credit, often following SEC 2a-7 guidelines.

At the end of a non-cash collateral agreement, the lender and its lending agent return the collateral in exchange for the security and will earn a pre-negotiated lending fee on the posted collateral. However, in a cash collateral agreement, the lender returns the collateral (in exchange for the security) and provides a rebate to the borrower. The rebate is an agreed-upon interest rate for holding the collateral and is lowered by a “demand spread,” a function of the supply/demand characteristics of the loaned security. The demand spread is frequently higher than the interest owed on the collateral, resulting in a negative rebate rate.

The revenue generated by the lending agent is summed up by the demand spread and the reinvestment spread net of rebate fees. The incremental return is added to the return of the overall portfolio and can off-set administrative and management fees. The lending agent arranges a revenue-sharing split with the lender, ranging from 50%/50% for smaller programs to 90% for the lender with larger programs.

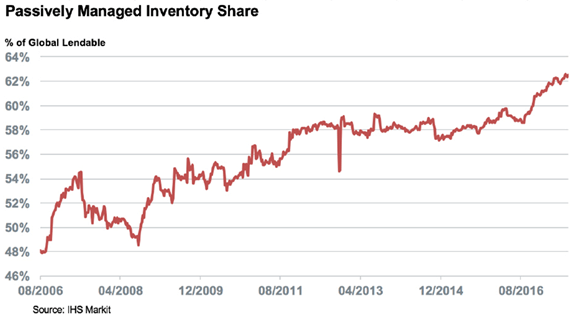

Today, the size of the lendable market stands at roughly $20 trillion and assets on loan are approximately $2 trillion. Of that, passively managed assets have grown to over 60% of inventory. Large funds with relatively passive portfolios, such as ETFs and index funds, are more likely than active funds to lend securities. The nature of their portfolios enables these funds to lend more securities for longer periods, making them preferred counterparties for their loans.

Best Practices

In evaluating a securities lending program, fund sponsors should focus on the ability of the lending agent to mitigate the risks of cash collateral impairment and liquidity as well as counterparty exposure. The lending agent should promote operational discipline by implementing strict controls, audit procedures, and transparency to monitor the daily activities of the program.

Before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), cash collateral reinvestment guidelines were less stringent and lending agents sometimes reinvested in less liquid, longer-duration assets to enhance yields. During the crisis, some of those riskier investments became impaired, and lenders experienced massive losses in cash collateral investment pools.

Since the GFC, new regulations have put limits on riskier collateral reinvestments; however, the lender still needs to be prudent and ensure its lending agent has a detailed summary of the collateral reinvestment pool. The lending agent should provide an outline of eligible investments as well as guidelines regarding the credit quality, liquidity, and maturity of the investments. It should maintain strict risk management guidelines to avoid impairment, such as frequent compliance checks on reinvestments and stress tests to ensure that the return from the reinvested collateral exceeds the loan rebate. The agent should also seek to ensure that the maturity of the reinvestments closely matches the duration of the loans in order to diminish the liquidity risk, ensuring that cash will be available to settle trades.

In monitoring counter-party risk, the lending agent should review the financial condition of the borrower. The agent should follow a daily mark-to-market process for the transaction as well as ensure over-collateralization of the loan. The lending agent may provide indemnification provisions to the securities lending program, which would be triggered if the collateral is not sufficient to cover a default by the borrower; the lending agent would purchase the securities or provide an equivalent cash value. Fund sponsors should be aware of what indemnifications are provided and understand what protections they offer.

As with any investing program, there is no free lunch. The benefits of incremental returns and lowered fees come with risks. In considering a lending strategy, investors need to be acutely aware of the lending agent’s risk management program to make sure their passive strategies successfully do what they were meant to do: track the index.