As capital markets assumptions have declined for most asset classes, institutional investors are increasingly interested in real estate and infrastructure debt as they pursue return-seeking assets. This blog post, which summarizes our full paper on the topic available via the link above, discusses key aspects of real estate and infrastructure debt, including investment structures, market size, and implementation considerations.

Real Estate Debt

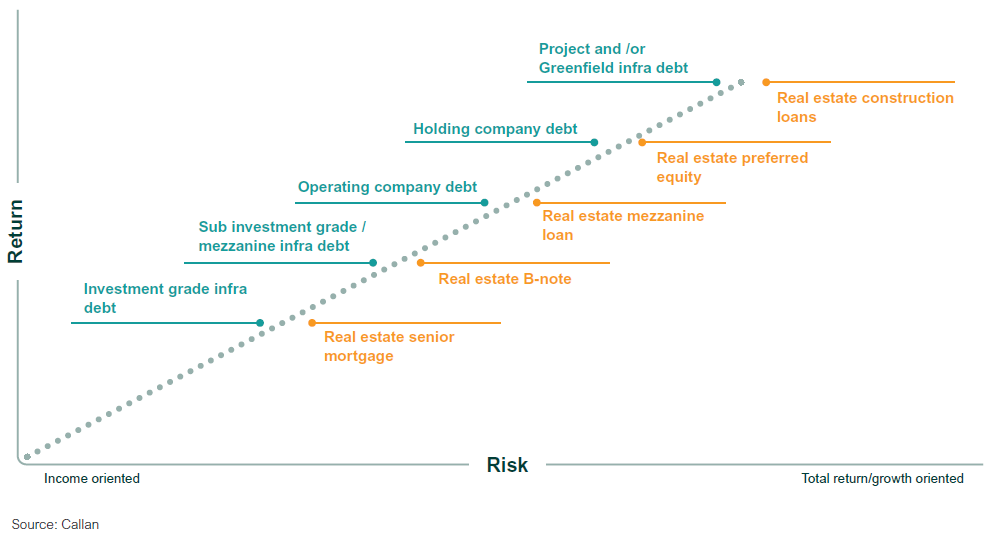

Commercial property real estate debt is lending on offices, retail locations, multi-family and single-family homes for rent, industrial facilities, self-storage locations, hotels, and other types of commercial properties. It does not include lending on single-family homes, i.e., residential mortgage-backed securities. Loan types are senior mortgages, B-notes, mezzanine loans, preferred equity, risk-retention bonds, construction loans, and commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS).

Outstanding maturities in the U.S. commercial real estate debt market totaled approximately $5 trillion as of Dec. 31, 2020, with $450–$500 billion of maturities each year on average. Half of all commercial mortgage debt is held by commercial banks, followed by insurance companies, securitized vehicles, and government-sponsored enterprises (or GSEs, including the Federal National Mortgage Association aka Fannie Mae and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation aka Freddie Mac).

Infrastructure Debt

Infrastructure includes utilities, transportation, power, energy, communications, water/waste, and social assets. The most common types of debt are investment-grade, sub-investment grade, operating company, holding company, mezzanine, and project/greenfield (or construction). There is significant public sector financing activity in the U.S. infrastructure lending market, which limits opportunities for private lenders. This may be changing as the sector matures, potentially creating more opportunities for private capital.

The global market for infrastructure project lending is estimated to be approximately $600 billion annually; this figure understates the market because a significant amount of infrastructure lending is done by global commercial banks as part of their project finance departments.

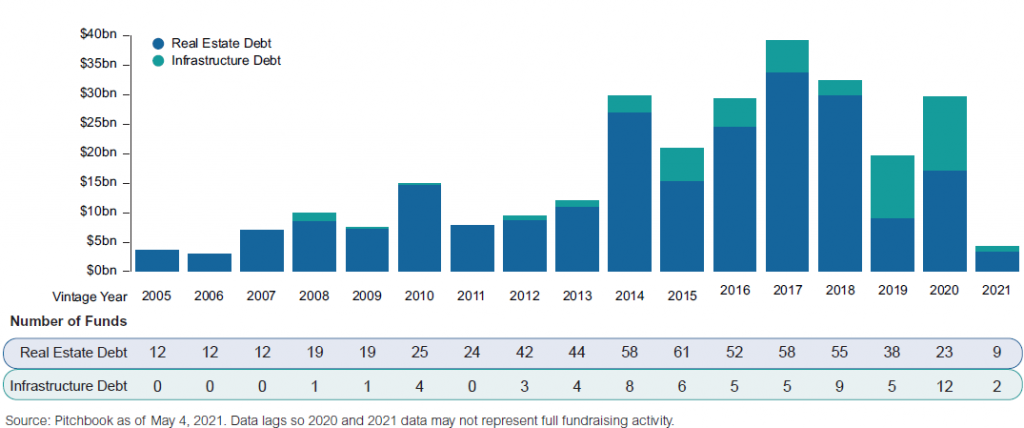

But insurance companies have been active lenders in the sector since the 1980s and are starting to offer infrastructure debt separate accounts and infrastructure debt funds to institutional investors. Infrastructure debt funds are lending on newer sectors such as digital (e.g., communications and data storage/transmission assets) and energy transition, which are more private equity-like and may have cash flows that are less reliant on contractual obligations or are at more risk of substitution/obsolescence than traditional infrastructure assets (e.g., utilities). Due to the complexity of the asset class and the dominance of banks, there are far fewer investment managers in infrastructure debt than real estate lending.

Risk and Return

Investors have a range of risk and return options available for real estate and infrastructure debt investments, from more conservative opportunities such as lending on stabilized real assets with known cash-flow profiles to higher risk-and-return strategies such as lending on development/greenfield assets for infrastructure.

Performance of Real Estate and Infrastructure Debt

Real estate debt as an asset class is most correlated to corporate and government bonds and less correlated to stocks. Similarly, infrastructure debt has a high correlation to investment grade corporate debt and U.S. Treasuries. There is no generally accepted benchmark for either real estate or infrastructure debt, as strategies vary across the risk/return spectrum. Investors should consider the purpose of the investment in their portfolio; if it serves as a fixed income substitute it would have a different benchmark than if it is a component of a private credit allocation or part of a real assets allocation.

Implementation

Real estate debt and infrastructure debt investments typically do not comprise a large part of broad private credit or fixed income mandates. Instead, institutional investors need to select managers with the specialized teams and expertise required to source, make, and manage real estate and infrastructure loans. Callan observes that investors need to make a defined, strategic portfolio allocation to incorporate real estate debt or infrastructure debt, either as part of a fixed income allocation or as part of a real estate/real assets allocation.

Most investors access this space through open-end or closed-end funds. Some investors can implement the strategy with separate accounts or make loans directly with internal staff. Investors should understand that infrastructure debt has a significantly smaller universe and shorter history than real estate debt.

Conclusion

Real estate and infrastructure debt both offer compelling risk/return characteristics that make them appealing as a portfolio return enhancer and/or diversifier. Investors should understand the fundamental differences between the two asset types. Real estate debt is more established than infrastructure debt with a wider range of managers, strategies, and vehicles to choose from, many of which have long-term track records.

The two asset types share many similarities, including a wide array of risk/return options. They also require specialized teams to implement, and the majority of investors will have to access these asset classes through open-end or closed-end funds. Both real estate and infrastructure debt lack a generally accepted benchmark, as strategies vary across the risk/return spectrum. Investors should consider the purpose this kind of debt serves in the portfolio to identify an appropriate benchmark: whether it is being used as a fixed income substitute, a component of a private credit allocation, or as part of a real assets allocation. Investors will need to make a strategic allocation to either of these asset classes for it to have an impact on their portfolio.