Recent economic reports have prompted fears that prices in the U.S. are about to take off. Concerns that pandemic-related supply bottlenecks, combined with increased consumer demand due to unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus, would lead to an undesirable jump in inflation seem to be, at least preliminarily, materializing. While increasing costs have been widespread, the greatest opportunity for sustained price increases lies in the labor market and the possibility of a wage-price spiral.

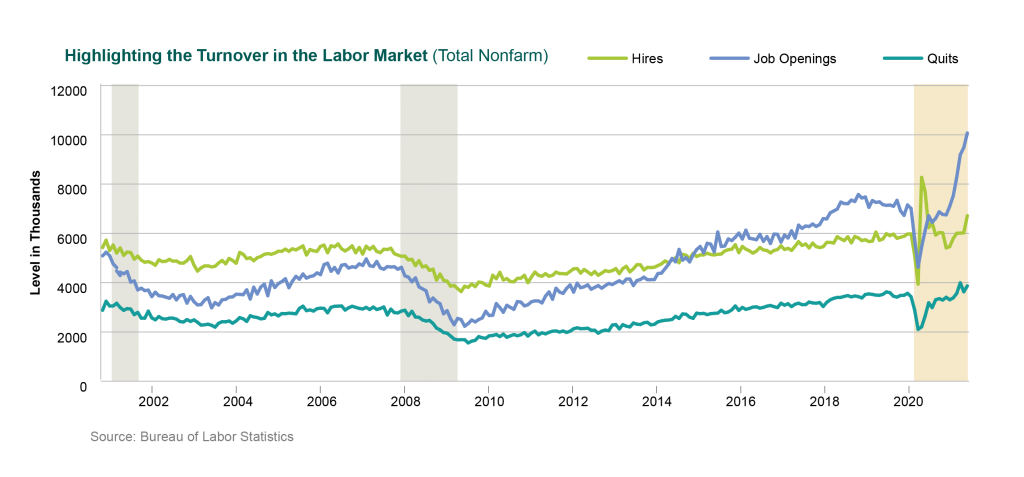

The August Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS), which the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) conducts as a complement to the unemployment report, highlighted these inflation fears. The report showed that total nonfarm job openings are at their highest level since the survey was started in 2000. This is true even though hiring has returned to pre-pandemic levels, indicating employers are finding labor in short supply. Workers seem to recognize their current value as “quits” are also near an all-time high, demonstrating they are confident they can improve their positions, including their compensation, by moving to new employers. Taken together, these statistics could signal a trend of increasing compensation driving more widespread inflation.

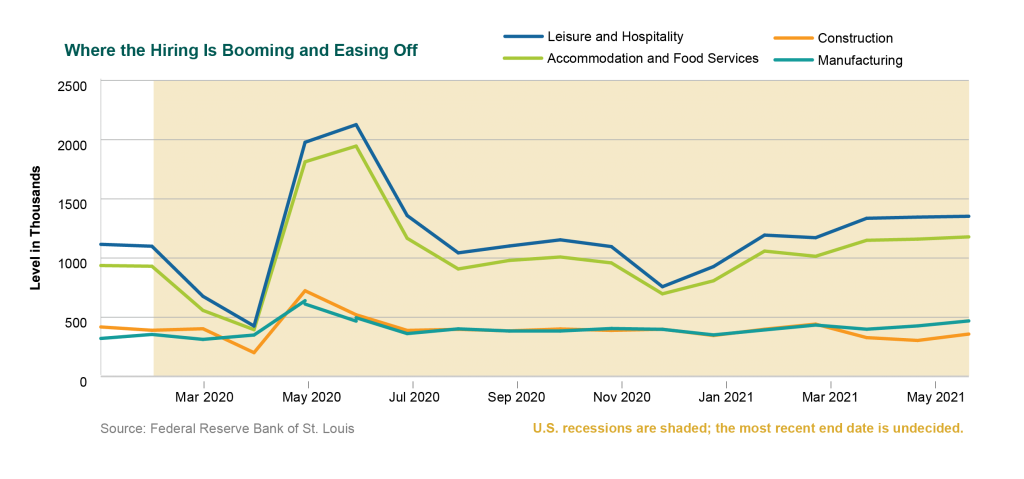

While the data in the survey are startling, underlying trends are more comforting. First, hiring is highly industry-dependent. The two industries that suffered the most from the pandemic lockdowns, Leisure and Hospitality and Accommodation and Food Services, are the greatest beneficiaries of the hiring recovery. Conversely, Manufacturing and Construction, which weathered restrictions relatively well, have seen hiring flatline since the middle of last year.

Second, while unemployment has fallen dramatically from its peak, it is still well above its pre-pandemic levels. The jobless rate was down to 3.5% in February 2020 before it rose to 14.8% two months later. In July it fell to 5.4%, but this is still nearly two percentage points higher than prior to the lockdowns.

Not only are there high numbers of unemployed workers, but there is also turnover within the group that is employed. Initial claims for unemployment have subsided since they peaked at over 6 million in April 2020. While they have fallen substantially since then, they have been hovering around 400,000 for weeks. The last time they were this high was early in 2012 when the economy was still recovering from the impact of the Global Financial Crisis. For most of the last five years they have bounced between 200,000 and 250,000. The elevated levels of both unemployment and employment turnover suggest that there is still a significant amount of labor on the sidelines.

A key question is what might be keeping people from going back to work. Some economists argue that expanded unemployment benefits have discouraged workers from returning. So far the evidence has been mostly anecdotal, but as more states stop offering these benefits, data to support or refute this argument will become available.

The hiring gap may also reflect how quickly unemployed workers are ready to reenter the workforce. Those not responding to openings now may more readily join the workforce later. The reasons often cited include concern about exposure to the virus at work and the need to care for children given the limited availability of child care and school.

Evidence of this is limited, but some information can be inferred from recent statistics. One metric is the number of workers who are “marginally attached” to the labor force but not “discouraged” workers. Marginally attached workers “includes those who did not actively look for work in the prior four weeks for such reasons as school or family responsibilities, ill health, and transportation problems,” according to the BLS. Although people who fall in this group may be members for reasons other than family responsibilities, these statistics are still likely to be representative of those with family responsibilities that interfere with their ability to work. Not surprisingly the numbers peaked in April 2020 during the depths of the pandemic. They subsequently started falling as reopenings began in the summer of 2020, and they are not historically high. Higher levels were experienced continuously from 2011 into 2015. As the economy returns to normal (including expanding child care options), the number of marginally attached workers is likely to decline more, thus expanding the labor force and limiting the pressure on wages.

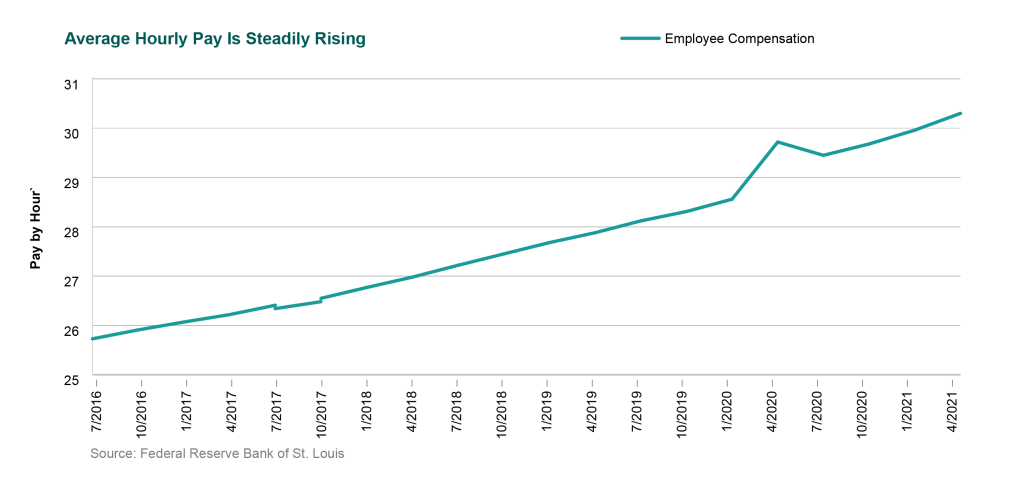

Finally, perhaps the best indicator of an imbalance between the supply and demand of labor is the rate at which compensation is rising. Average compensation rose substantially at the beginning of the pandemic as many low-wage workers performed jobs affected by pandemic lockdowns. The average then dropped as lower wage workers returned. Since 3Q20, earnings have increased at a rate that is only modestly above the trend that preceded the pandemic.

The employment situation remains uncertain as the economy as a whole moves toward normalization. Fears of a labor shortage resulting in substantial increases in compensation that in turn fuel high levels of inflation may ultimately be realized. While there are early signs that this is occurring, this result is far from assured, and more data will be needed to draw firmer conclusions.