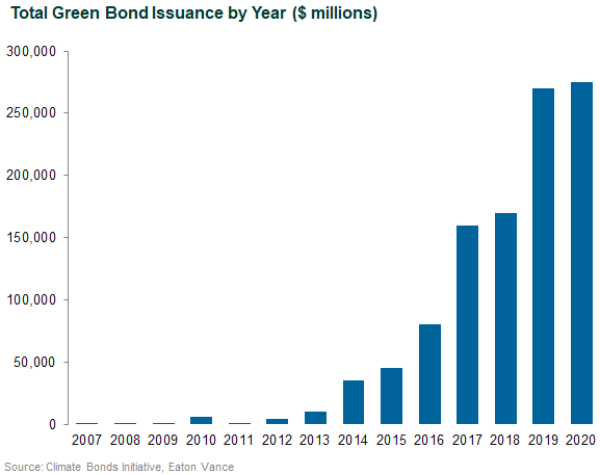

Issuance of green bonds, which finance projects with a positive environmental impact, has exploded in recent years, and the space is expected to continue to show steady growth. Callan believes that active management is important for institutional investors that seek exposure to this segment of the market.

The first green bond was issued by the European Investment Bank in 2007 to finance renewable energy and energy efficiency projects (a focus on climate change is common for these types of bonds). Issuance is now commonly seen by sovereign entities, corporations, and from across municipal and securitized sectors.

The green bond market reached $1 trillion in outstanding debt at the end of 2020, according to the Climate Bonds Green Bond database. We expect issuance to continue to gain momentum given robust demand from investors that are keen to address climate change concerns by helping finance the global transition to cleaner energy.

A common challenge for those investing in green bonds is that there is no uniform set of requirements or standards. This makes analysis and monitoring more critical as a simple “green” label is no assurance that the use of proceeds, or the issuer itself, meets desired objectives.

The International Capital Markets Association’s Green Bond Principles is one framework, but compliance is voluntary. These principles were updated in 2018 and provide guidelines for disclosures from issuers. Separately, the Climate Bond Initiative (CBI) provides a green bond certification for issuers, and while it is considered to be the gold standard, there is a fee for this certification, and an “approved verifier” needs to ensure that the bond meets the required CBI standards. This is a difficult hurdle for some smaller issuers. Its standards are designed to ensure that issuance aligns with the Paris Climate Agreement to limit climate warming to less than 2 degrees Celsius.

Many are working hard to develop a widely accepted set of standards, but this important goal remains a work in progress. As a result, an important nuance has emerged: a differentiation between “labeled” and “unlabeled” green bonds. Labeled green bonds must meet certain certifications, as noted above. But active managers should have the resources and skills to ascertain whether a bond meets its environmental impact objectives regardless of the label it carries. These two examples provide some context on the challenge:

- A labeled green bond that is “gray”: A Spanish oil and gas company issued a green bond in which proceeds were used to finance energy efficiency initiatives. However, some market participants may consider financing a bond that improves efficiency for a fossil fuel company as being incongruent with “green” goals and objectives.

- An unlabeled bond that is “green”: A privately owned mobile home park provides affordable housing for local workers and residents in a high-income area. It issued a bond, and a portion of the proceeds were earmarked for solar panels atop existing parking structures and buildings to lower electricity costs for residents. This issuance, which was not labeled “green,” provides positive societal and environmental impacts and thus fits well for a “green-minded” investor.

Bottom line: Active fixed income management is key to identifying and analyzing green bond projects and issuers in the absence of global standards. Further, we believe it is important to evaluate the ESG characteristics of the issuer. If an issuer does not meet minimum ESG standards, then the use of proceeds may or may not make the investment appropriate for ESG-minded investors. Also, active management allows for relative value considerations to be incorporated into security selection decisions. In some cases, green bonds may command a premium due solely to the label. Finally, there is no assurance that a green bond issuer will use the proceeds as promised, so ongoing monitoring is essential.