The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has not been shared equally by all Americans, as low-income communities—particularly communities of color—are more likely to contract COVID-19, more likely to die from it, and more likely to become unemployed because of it.

Now, these same vulnerable communities face an increased risk of eviction, if the federal eviction moratorium is allowed to expire at the end of June. An analysis by The Aspen Institute—an educational and policy studies nonprofit—estimated that a total of 30 to 40 million renters are at risk of being forced from their residences.

The Biden administration’s $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief package originally would have extended the eviction moratorium through September 2021, but because of the way in which it was passed, that provision was dropped. It did include $27.5 billion in renter assistance plus $5 billion for utilities payment support and $5 billion to help relieve the strain of homelessness.

While eviction moratoriums keep people housed temporarily, they effectively delay the financial stress on renters. When moratoriums are eventually lifted, months of accumulated debt will still be due, and millions of renters will not have the means to pay. Moody’s Analytics estimated that this outstanding debt totaled as much as $70 billion at the end of 2020.

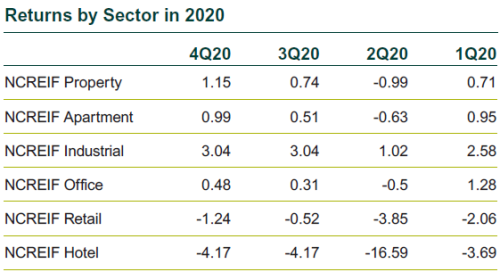

Despite this, the multifamily property sector has been resilient, compared to other real estate property types that have struggled amid the pandemic. While performance can vary significantly by geography and sub-type—gateway markets have underperformed relative to secondary markets, and high-rise apartments have underperformed relative to garden-style apartments—occupancy, rent collections, and valuations have not been significantly impacted by the pandemic. Returns for the NCREIF Property Index Apartment subindex have remained relatively flat throughout the pandemic, at -0.6% for 2Q20, 0.5% for 3Q, and 1.0% for 4Q. This is in stark contrast to the 2Q declines in the Hotel and Retail subindices, which fell 16.6% and 3.9%, respectively. Echoing this confidence, the National Multifamily Housing Council’s (NMHC) monthly rent tracker has reported only a modest decline in rent collections, with 89% of apartment households paying rent as of Jan. 20, 2021, compared with 90% in the prior month and 91% in January 2020.

The disconnect between the institutional real estate market and research suggesting severe renter distress may seem counterintuitive, but it is ultimately tied to tenant profile. Apartment properties held in institutional portfolios are generally occupied by middle- and high-income earners who have remained employed during the pandemic and continue to pay their rent on time. The NMHC rent tracker is based on data from 11.6 million professionally managed units and does not capture rent collection data from non-institutional landlords. Importantly, more than 50% of renters with at-risk wages due to the COVID-19 pandemic live in single-family or small multifamily rentals with less than four units, according to research by Harvard University. This suggests at least some of the challenges in rent collection are being faced by smaller properties, which are generally not found in institutional real estate portfolios.

Of course, no landlord wants to remove people from their homes. Evicting tenants means that landlords will not be collecting any income from their now-vacant units until those tenants are replaced. Vacancies are even harder to fill during a public health crisis, as would-be renters opt to stay where they are. About one full year into the pandemic, some landlords are owed months of back rent and may be struggling to meet their own obligations, including debt service, property taxes, and operating and maintenance expenses. Landlords are holding on in hopes that government aid will help them address the accumulating rent debt. However, the $25 billion in renter assistance issued in December combined with the additional $25 billion from the new relief bill does not cover the estimated $70 billion in outstanding debt. For now, most landlords are establishing payment plans with tenants to recover at least some of the rent they are owed. In some cases, eviction filings are proceeding for reasons other than non-payment of rent.

It is in the best interest of renters, landlords, and investors to keep people in their homes. A near-term eviction crisis is far from a certainty, and will depend on a number of factors including the impact of the $1.9 trillion relief plan, whether the federal eviction moratorium is extended again, the COVID-19 vaccine rollout, and the resilience and rebound of the labor market. While most institutional real estate portfolios have not experienced meaningful declines in rent collections and are unlikely to be significantly impacted by the potential eviction crisis, a wave of evictions would have substantial and long-lasting negative consequences for all parties involved as well as the broader economy and society.

Institutional investors should continue to closely monitor rent collections within their multifamily portfolios, as decreases in collections may indicate financial distress among tenants. Additionally, investors should engage with their real estate investment managers to understand how non-payment of rent is treated and how tenants could be displaced at properties within their portfolios.