The growing number of corporations and institutional investors pledging to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions—as well as a heightened focus on energy independence—has increased the visibility of what are called “energy-transition investments.” This blog post will provide a summary of energy-transition investments; for a more detailed analysis of this emerging sub-sector in infrastructure, please see my white paper on the subject available at the link above.

Energy-Transition Investments: A Focus on Low-Carbon Energy

Energy-transition investments typically aim to produce, store, or transport low-carbon energy. They include both traditional investments such as onshore wind, solar, and hydro power as well as newer options including offshore wind projects, batteries that store renewable energy and support overall grid stability, electric vehicle (EV) infrastructure, and low-emissions fuels.

Competing Forces at Work

While there are multiple forces driving interest in energy-transition investments, the sector faces some notable challenges in the current environment. Institutional investors analyzing this space need to understand both.

TAILWINDS

I. Current political landscape

The war in Ukraine has compelled Europe to re-examine the source of its energy supply. Renewable power contributes to a country’s energy independence and potentially provides political benefits, which is especially attractive at this time of disruption in global energy markets.

II. Net-zero goals

Adoption of net-zero initiatives, by countries, companies, and investment managers, has led to increased support and demand for renewable sources of energy and encouraged consumers to use energy more efficiently.

III. Billions of dollars of funding

The Inflation Reduction Act signed into law in 2022 allocated $369 billion for energy security and climate change initiatives. The bill includes support for expanding the country’s energy independence with a decade of tax credits. These credits will provide a level of certainty to new renewables projects and extend these credits to battery storage for the first time, which will reduce the risk of new projects to supply clean power to the grid in the U.S.

IV. New European incentives

The United Nations has identified 17 sustainable development goals. European regulators have provided guidance, through the EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation, for fund managers that wish to highlight their commitment to these various environmental, social, and governance (ESG) goals.

HEADWINDS

I. Interconnection: How renewable power is delivered to the grid

The process to develop a renewables project can be complex: from assembling the site, securing materials, arranging financing and tax credits, and constructing the actual wind or solar farm. Another important, and often less discussed, milestone for a renewable project is the interconnection agreement that allows the renewable energy producer to supply power to the grid. In some regions, there is congestion to supply power to the grid, which can result in curtailment—where a renewable power seller is not allowed to deliver all of its power to the grid—and this negatively impacts financial performance.

II. Economic slowdown and anti-ESG sentiment

There is growing pushback against corporate ESG initiatives, with some states criticizing the use of ESG principles in the investing process. If the economy enters a recession, corporations may consider delaying net-zero goals or reducing expenditures on capital investment related to energy-transition projects.

III. Supply chain issues

The International Energy Agency (IEA) found that global battery and minerals supply chains have to expand 10-fold to meet projected critical minerals needs by 2030 to support global net-zero emissions goals.

Other research by the IEA finds that solar power plants, wind farms, and EVs generally need more minerals to build compared to fossil fuel-based equivalents. According to the IEA, “Since 2010 the average amount of minerals needed for a new unit of power generation capacity has increased by 50% as the share of renewables in new investment has risen.” For lithium, cobalt, and rare earth elements, production is concentrated in a handful of countries; in some instances, one country produces about half of global output. Processing is even more concentrated: China’s share of refining is approximately 35% for nickel, 50%-70% for lithium and cobalt, and nearly 90% for rare earth elements. According to the IEA, “High levels of concentration, compounded by complex supply chains, increase the risks that could arise from physical disruption, trade restrictions, or other developments in major producing countries.”

IV. Increased capital

With all of the positive tailwinds for investment in energy transition, significant capital is being raised. This has put upward pressure on prices for traditional wind and solar investments in the past 10 years, which reduced ultimate investor returns on the whole. It is reasonable to expect competition to acquire energy-transition investments could similarly increase prices, which could reduce investor returns in the long run.

V. Market, technology, and construction risk

Market risk is a consideration with any investment; as an example, businesses related to EVs (e.g., charging stations) are a growth area, with a variety of new companies/services, and there is potential for competition to erode pricing margins and create winners/losers. Technology/construction is also a consideration with any new investment. While onshore wind and solar installations have been operating for over two decades and have proven to be attractive investments on the whole, offshore wind investments, which are seeing growing interest, require complex planning, permitting, construction, and maintenance activity.

Conclusion

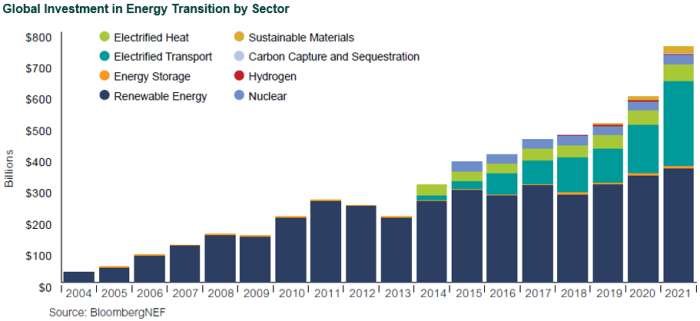

Energy-transition investments have seen a significant increase in interest, with capital flowing to the sector nearly tripling over the last decade. The growth stems from a combination of attention to climate change and renewed focus on energy independence, as well as an expanding investment opportunity set. The breadth of energy-transition investments has also expanded. Traditional investments in the sector included renewables, but recently the types of investments have grown to include areas such as offshore wind projects, EV infrastructure, and low-emissions fuels.

The sector also faces notable headwinds and risks, including anti-ESG sentiment and supply-chain issues, technology and construction risks, and market-related risks such as increasing competition in the EV space.

Disclosures

The Callan Institute (the “Institute”) is, and will be, the sole owner and copyright holder of all material prepared or developed by the Institute. No party has the right to reproduce, revise, resell, disseminate externally, disseminate to any affiliate firms, or post on internal websites any part of any material prepared or developed by the Institute, without the Institute’s permission. Institute clients only have the right to utilize such material internally in their business.