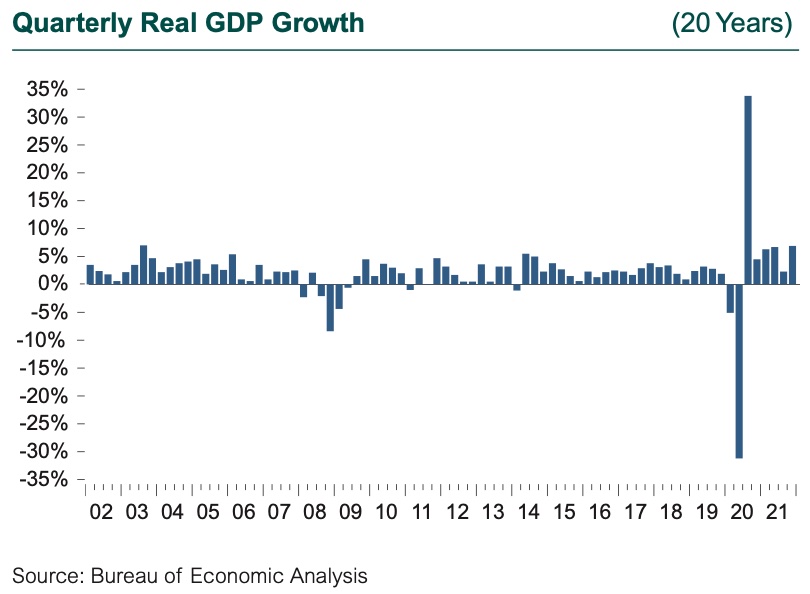

The fourth quarter of 2021 closed out another remarkable year for the U.S. economy following the wild ride through the pandemic and the recovery, a cycle that began in earnest in February 2020. U.S. GDP notched an incredibly strong 6.9% quarterly gain (4Q over 4Q), which translates to annual growth of 5.7% over 2020. We have not seen such growth since the Ronald Reagan administration, following the consecutive recessions of 1980 and 1982 induced in part to wring double-digit inflation out of the economy.

A short detour into monetary policy history is relevant here. The advent of current monetary policy began during the Reagan administration under Fed Chair Paul Volcker, although he was appointed by Jimmy Carter. Alan Greenspan took on the mantel of “monetarist” from Volcker and enshrined the discipline into Fed policy. That monetarist bent was then modified seriously by Ben Bernanke to address the Global Financial Crisis, when a zero interest rate policy was employed both in the U.S. and by most central banks around the world to rescue the global economy from collapse. Zero rates were combined with massive monetary intervention through the purchase of bonds to keep rates low and infuse liquidity into the system. Emboldened by what we learned in the GFC and the innovation in monetary intervention tools we developed, we applied zero rates with substantial monetary intervention to rescue the global economy again at the onset of the pandemic. After two years and a complete recovery to pre-pandemic GDP levels, the question now is what is next for the post-pandemic economy.

The Outlook for the U.S. Economy

At the risk of not sounding an alarm, we believe supply chains will untangle, labor markets will slowly equilibrate, and supply and demand will line up the economy’s production function and the consumer’s normalizing demand for goods, services, food, and shelter. The Fed has begun tapering its asset purchases intended to supply liquidity to capital markets, and it is strongly signaling that interest rates will rise, with three hikes in the Fed Funds rate in 2022 articulated in the last FOMC meeting in January (the market is discounting four hikes). As policy is withdrawn, the global economy will move to stand on its own two feet, complete with the cycles of growth and recession fully expected in a market system. Top of mind for many is inflation, which hit a peak of 7% in 4Q21. There is now an entire generation of market participants who have never experienced sustained inflation, which was last seen in the early 1980s.

After starting 2021 in the shadow of renewed lockdowns in 4Q20 following then-record spikes in pandemic infections and hospitalizations, the global economy and the U.S. in particular began a spurt of optimistic growth in the spring, and many measures of economic growth took off: consumption, business spending, production, travel, home-buying (which had started surging in 2020), and the opening of retail trade, dining, hospitality, and recreation. U.S. GDP surged in the second and fourth quarters, and the increase of 5.7% for 2021 compares to the 3.6% decline in 2020. Much has been made of the supply chain issues that have restricted output and the supply of goods, the fundamental mismatch between job seekers and available jobs, and the impact of both on potential growth and inflation. We believe the remaining supply chain issues will be ironed out over the course of 2022, increasing the supply of goods and relieving the pressure on prices. We also believe that the labor market will adjust, but that the process may be slower than that for goods and services, and that higher wages may be a feature of the U.S. economy for at least another year and perhaps in to 2023. The job segments most disrupted by the pandemic—retail, wholesale trade, transportation services, hospitality, education, state and local government—are those facing the most obstacles to rehiring at prevailing wages.

A couple of key metrics point toward a slowdown from the manic growth of 2021. First, within GDP, the building of inventory accounted for 4.9% of the 6.9% growth for 4Q21. Inventories built now boost current GDP, but suggest downward pressure on prices of those inventoried goods and slower growth from future production. Second, one of the key forward-looking indicators is the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), which surveys planned activity by market participants—new orders, output, input prices, employment—and covers both goods and services. The PMI for new orders around the globe went flat in August 2021 and stayed flat through December, as first the Delta then the Omicron variants spooked consumers and businesses. Third, at the start of 2022, the PMI for new orders has fallen sharply, driven by weakness emerging in the order data in China and the U.S., two of the biggest global economies.