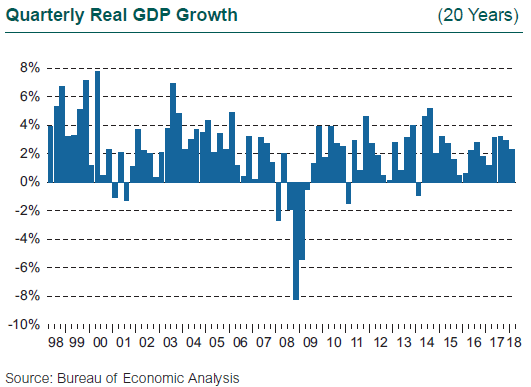

After a weak first quarter, the U.S. economy closed out 2017 with decent momentum, as GDP grew at a robust 3% annualized rate for the remaining three quarters. The first quarter of 2018 will likely be remembered for its sudden, brief correction and the return of volatility. True to form, however, the U.S. economy continued to post solid growth, ignoring the uncertainty introduced by the stock market gyrations, just as it ignored the geopolitical uncertainty humming in the background over the last 18 months.

The first quarter’s 2.3% gain was a step down from the string of 3% increases but actually higher than most estimates. The unexpected strength in first-quarter GDP growth came from net exports (imports were less than expected, exports were greater), from fixed investment in buildings and capital, and from government expenditures.

Growth expectations had been tempered by the depletion of inventories and signs of slowing consumer spending at the end of 2017. However, consumers remained optimistic during the first quarter, even after the market turmoil in February, with the University of Michigan’s Index of Consumer Confidence hitting a 14-year high in March.

Strong labor markets are a clear contributor to confidence. In the U.S., the unemployment rate fell to 4.1% in the fourth quarter of 2017, a generational low, and remained at that rate through the first quarter of 2018. Initial claims for unemployment insurance have fallen to the lowest level since 1969.

The slow burn in the current expansion may enable it to continue for some time. This recovery is one of the longest on record at 105 months, but also one of the slowest, with average GDP growth in the U.S. of just 2.2%. Expansions do not die of old age; rather they collapse under the weight of imbalances that become untenable.

Thus far into this slow burn, signs of severe imbalances are few, although several potential ones come to mind: tight labor markets, inflation, housing shortages in select urban areas, and rich asset prices kept aloft by the continued growth in the economy.

Inflation may finally be poised to become the problem we all expected to arise after years of sustained monetary and fiscal stimulus. The CPI-U notched a year-over-year gain of 2.4% in the first quarter, with core inflation reporting a 2.1% increase. While this sounds very modest, the CPI-U has been inching steadily upward since bottoming out in 2015, when oil prices collapsed.

One of the most profound conundrums has been the lack of wage pressure while the unemployment rate has steadily fallen to historically low levels. Average hourly earnings were stuck at 2% growth, and only recently has the rate of growth begun to rise. In fact, the report of wage growth coming in close to 3% in January was one of the catalysts cited for the spike in market volatility in early February, spurring fears of inflation among investors. Wage growth did not jump higher than 3% in February and March, but stronger wage growth will feed into core inflation. The Employment Cost Index, which includes benefit costs along with wages and salaries, rose 2.7% year-over-year in the first quarter, the highest rate of growth since 2007.

Barring another collapse in energy prices or a sudden downturn in global growth, inflation momentum will keep building. Continued growth and the potential pickup in inflation give the Fed cover for more interest rate hikes. One development of interest is the potential for an inverted yield curve. The Fed raised interest rates three times in 2017 and again in March 2018, which shifted the short end of the yield curve up, but the long end barely budged. As a result, the curve flattened substantially.

The Fed is telegraphing up to three more rate hikes this year, and if the long end of the curve remains anchored, the potential increases for the curve to invert, where yields on longer maturities are lower than those for shorter maturities. An inverted yield curve can suggest the onset of recession: investors bid up the price of longer-dated debt (driving down yields) in anticipation of a slowing economy, leading to an expected cut in interest rates and increased demand for bonds. An inverted yield curve does not cause a recession, but it does reflect the opinions and concerns of market participants.

Complicating the story here is that while the Fed has begun to unwind its balance sheet, which suggests it could be selling bonds and putting upward pressure on rates, demand remains strong on the long end of the yield curve, as yields in the U.S. are substantially above those overseas.