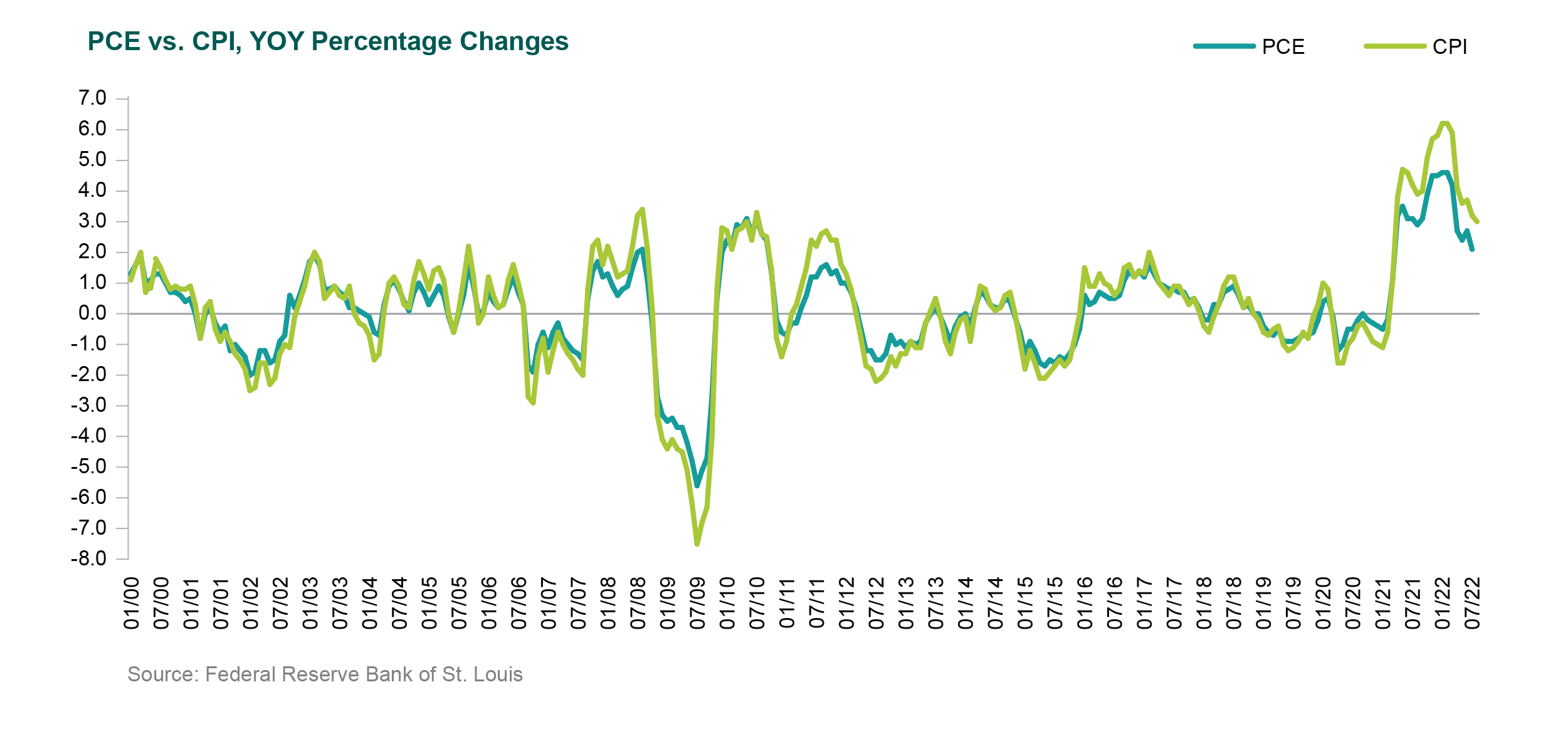

By any measure, inflation is at historic highs in the United States. Its seemingly relentless rise has been stoked by strong consumer demand fueled by low interest rates and government stimulus; supply-chain disruptions; and higher food, energy, and commodity prices stemming from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The cost of shelter has also had a significant effect on inflation more recently. Finally, wage increases, which have been spurred by the strong job market, are reflected in the prices of goods and services and are thus another driver of inflation.

But there are actually two primary measures of inflation: the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCE). What are the differences between the two? Why does the Fed prefer one over the other? And what are some of the issues that may drive future inflation increases?

The CPI is released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (see here for details and the latest release), and the PCE is issued by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (here for details). While both measure inflation based on a basket of goods, there are subtle differences between the indices:

- Sources of data: The CPI uses data from household surveys; the PCE uses data from the gross domestic product report and from suppliers. In addition, the PCE measures goods and services bought by all U.S. households and nonprofits. The CPI only accounts for all urban households.

- Coverage: The CPI only covers out-of-pocket expenditures on goods and services purchased. It excludes other expenditures that are not paid for directly (e.g., medical care paid for by employer-provided insurance, Medicare, or Medicaid). These are included in the PCE.

- Formulas: The CPI formula is more likely to be affected by categories with wide price swings such as computers and gasoline. The PCE calculations smooth out these price swings, which makes the PCE less volatile than the CPI.

In January 2023, the BLS plans to start updating weights for the CPI annually based on consumer expenditure data from a single year. This reflects a change from the prior practice of updating weights every two years using two years of expenditure data.

In January 2012, the Federal Reserve announced that it would use the PCE as its primary measure of inflation, preferring it for three primary reasons:

- The expenditure weights in the PCE can change as people substitute away from some goods and services toward others. Thus, if the price of bread goes up, people buy less bread, and the PCE uses a new basket of goods that accounts for people buying less bread. The CPI, however, is less fluid in response to changing consumer preferences.

- The PCE includes more comprehensive coverage of goods and services.

- PCE data can be revised more extensively than the CPI, which can only be adjusted for seasonal factors and only for the previous five years.

Markets are worried about inflation because its current level is well above the Federal Reserve’s long-run inflation rate objective of 2% (on the core PCE Index, which excludes volatile fuel and energy prices). It has also been more persistent and broad-based than many expected and has led to an aggressive series of rate hikes by the Fed.

In summary, the CPI represents a basket of goods and services that a consumer would buy without making substitution changes when prices change. The PCE encompasses a broader range of goods and services than the CPI, from a broader range of buyers. It tries to track what is actually purchased, and represents how consumers change their buying patterns when relative prices change. This leads to smoother price changes in the PCE and typically lower levels of reported inflation, at least as experienced by consumers.