Over the last year or so, the growth of BBB-rated debt as a percentage of the overall investment-grade corporate bond market has sparked significant debate among investors. The key issue: the implications to the fixed income market should bonds at the lowest rung of the investment-grade ladder be downgraded.

Background: There are two distinct sections of the corporate bond market, based on the assessments produced by agencies that rate bonds:

- Investment-grade segment: composed of less risky bonds issued by corporations with a high probability of paying interest and returning principal to debt-holders

- High-yield segment: also known as “junk bonds,” composed of riskier securities issued by corporations with a higher probability of the issuer failing to make an interest or principal payment

Demarcating the two segments is the BBB rating, which indicates the highest level of risk in the investment-grade spectrum. Thus, a whole notch downgrade from BBB to BB moves an issuer’s status from investment grade to high yield. These “fallen angels” experience a material drop in price for the same bond in order to compensate investors for the additional risk while increasing the borrowing costs for the company. The new high-yield rating also shifts market access to a different set of investors. These changes are key pieces of the current discussion.

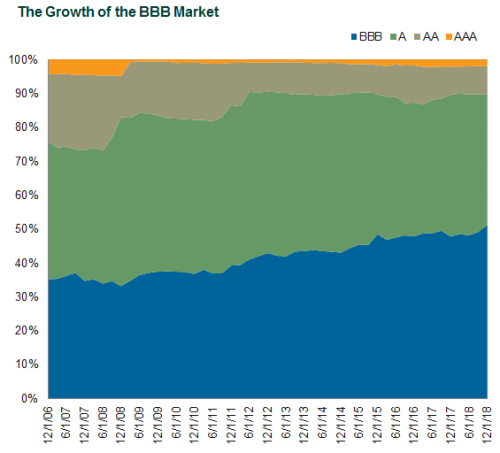

Much of the growth in the BBB market occurred following the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), when the U.S. Federal Reserve cut interest rates to nearly zero and introduced quantitative easing. These accommodative monetary policies brought about historically low costs of borrowing that incentivized U.S. companies to issue record amounts of debt, while also pursuing significant debt-funded M&A deals. The access to cheap funding led to a sharp rise in the amount of investment-grade U.S. corporate debt issued (from $1.7 trillion to $5.1 trillion, according to Bloomberg Barclays) between 2006 and 2018. BBBs as a percentage of the Bloomberg Barclays US Corporate Investment Grade Index grew from 35% to 51% during this same period.

Source: Bloomberg Barclays

With the slowing U.S. economy posing challenges to companies, scrutiny about this market has risen significantly. The key concern: Can these BBB-rated corporations retain their investment-grade ratings? And, if not, what impact will a large number of fallen angels have on credit markets?

The Arguments: On one side, there are investors increasingly worried about the weight of BBBs and the ability of the high yield market to absorb a wave of potential downgrades. They argue ratings agencies have been lenient on corporations that have not followed plans to reduce their borrowings as the economy recovered from the GFC. Now, amid a weakening U.S. economic backdrop, these corporations’ diminished credit servicing abilities could lead to a wave of downgrades when rating agencies tighten their rating standards. Due to the current size of the high yield market ($1.2 trillion, according to Bloomberg Barclays), these investors argue that such downgrades could not be absorbed without triggering decreases in bond prices throughout the ratings spectrum, including investment grade. Furthermore, there are multiple BBB issuers that would, if downgraded, each represent more than 2% of the Bloomberg Barclays US Corporate High Yield Index, exacerbating their concerns about the ability of the market to absorb this potential new supply.

On the flip side, other investors argue that the likelihood of such an event is overblown, and the characteristics of the BBB market do not foreshadow a wave of downgrades. To start, the largest industries in the BBB market as a percentage of market value are Financials (12%) and Consumer Non-Cyclical (10%). After the GFC, rating agencies changed their methodology on how they viewed Financials and downgraded many large entities into the BBB bucket. However, they say, these companies are arguably better capitalized with healthier balance sheets post-GFC, and they may likely see credit upgrades rather than downgrades. Issuers in the Consumer Non-Cyclical industry have also been historically more resilient in times of economic slowdown due to their stable cash flow and lower sensitivity to discretionary spending.

In addition, proponents cite the historical reluctance by ratings agencies to downgrade issuers to below investment grade, as well as the actions available to issuers in order to increase their credit servicing ability. Such actions include cutting dividends to equity shareholders, reducing operating expenses, and selling non-essential assets. It is also argued that corporations have substantial incentives to stay investment grade given the significantly higher marginal costs of borrowing and lower demand from a smaller base of investors if their debt fell to junk levels.

Takeaway: Irrespective of which side offers the most compelling argument, the record size of the corporate bond market and the growth within it of BBB-rated securities mandates that fund sponsors assess their exposure in this asset class and how either scenario would impact their portfolios. It is also imperative that fund sponsors understand their managers’ viewpoints in regards to this asset class. After a 10-year bull market, the next 10 years may require investors to continue their stringent due diligence in order to minimize unwanted volatility.