The bond market is convinced a recession is inevitable in 2023. The yield curve is inverted, and this phenomenon has preceded every recession in modern history. This inversion occurs when yields on the short end of the curve are higher than yields on the long end. A normal yield curve is upward sloping, with higher yields offered for taking on debt with greater maturities. An inverted yield curve implies that investors expect interest rates to fall, and that holding longer-dated debt will provide a greater return as rates drop. Why would investors expect interest rates to fall? They believe that a recession is coming, and the Federal Reserve will cut interest rates to stimulate economic growth.

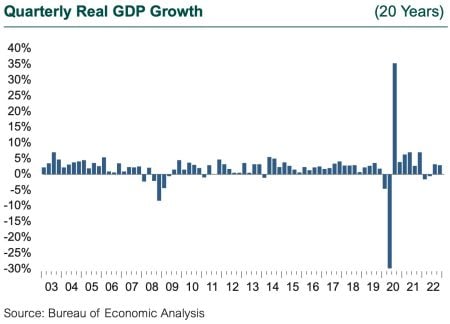

Last year was anything but normal for almost all measures of the capital markets, interest rates, inflation, and the economy. It may be reasonable to be a bit skeptical that the bond market has called this recession correctly. First, the U.S. economy suffered two quarters in a row of GDP loss “way back” in 1Q and 2Q22! A consecutive quarterly decline in GDP is often the rule of thumb used to invoke recession, but last year, such was not the case. The economy resumed robust growth with a solid 3.2% annualized gain in 3Q, and a 2.9% increase in 4Q. As a result, GDP advanced 2.1% for the year, following a strong 5.9% jump in 2021. Where was the growth in 4Q22 and for the year? Consumer spending on services, led by international travel, food services, accommodation, and health care. We also rebuilt inventories and increased investment in software and equipment. The one large drag was a decline in home construction, as mortgage rates shot up from the low 2% range to over 7% in a matter of months.

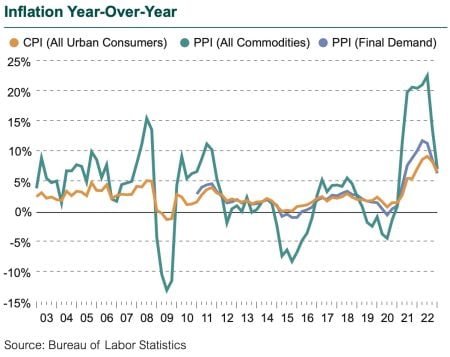

Inflation burned out of control by mid-year 2022. Faced with huge increases in the price of daily staples and durable goods like autos, consumers quickly redirected their spending away from goods suffering steep inflation, and spending on such goods within GDP actually declined during the year. This wasn’t always captured in the CPI; one of its failings as a measure of inflation is that it assumes a certain basket of goods will continue to be purchased at fixed weights even when prices shoot up. Clearly, higher prices for food staples and rent are impossible to avoid, but consumers substitute budget expenditures with great skill to counter price hikes. Inflation measured by the CPI-U rose sharply year-over-year, cresting at 9% by June, but the rate of increase in prices flattened completely in the second half of the year. So while the year-over-year increase for 4Q CPI hit 6.5%, the quarterly CPI for 4Q came in at 0% (change over 3Q). The problem for consumers and businesses is that even though CPI has stopped rising, prices are now “permanently” higher.

While a disconnect remains in the job market between those looking for work and the jobs offered by employers, the job market notched serious gains in net new jobs throughout the year, adding over 4.5 million. The level of employment finally surpassed the pre-pandemic peak in August 2022. Additions to the unemployment roll measured by weekly jobless claims continued to stay historically low, while continuing unemployment claims dropped from over 5 million at the start of 2021 to 1.7 million in December. Calendar year 2022 saw the lowest level of continuing claims in more than two decades.

With continued economic strength suggested by the robust job market and solid GDP growth, where is the concern over recession coming from in the bond market? The answer is a logic puzzle that can seem like a circular argument. The Fed raised rates quickly and by a large amount starting last March to battle the surge in inflation. The surge stemmed from supply chain dislocations as we emerged from the pandemic lockdown; from a surge in demand for workers, which drove wage growth; from a surge in demand from consumers; and then layered on top of these trends the disruption from the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The bond market suddenly “believed” in the Fed’s stated plans for interest rates through 2022, and yields moved quickly toward long-term equilibrium by mid-year 2022. The Fed’s primary tool to battle inflation is the Fed Funds rate. The premise is that higher rates cool demand for goods and services from all actors in the economy and wring inflation out of the economy. The reality is that higher rates appear to be working as advertised, as demand has lessened and inflation stopped rising month-to-month in the summer of 2022.

The inverted yield curve says the bond market believes the very success of the Fed’s inflation policy is now certain to cause recession, and then a reversal of interest rate policy to fight said recession. Perhaps the bond market does not believe that we will achieve the holy grail of Fed policy, which is to engineer a “soft landing” from the current economic expansion. It is true that we have never achieved a soft landing in the past, so the bond market may be justified in expecting that the Fed will overshoot and tip the U.S. into recession. Robust current economic indicators, especially in the labor market outside of technology, conflict with this market expectation.

Disclosures

The Callan Institute (the “Institute”) is, and will be, the sole owner and copyright holder of all material prepared or developed by the Institute. No party has the right to reproduce, revise, resell, disseminate externally, disseminate to any affiliate firms, or post on internal websites any part of any material prepared or developed by the Institute, without the Institute’s permission. Institute clients only have the right to utilize such material internally in their business.