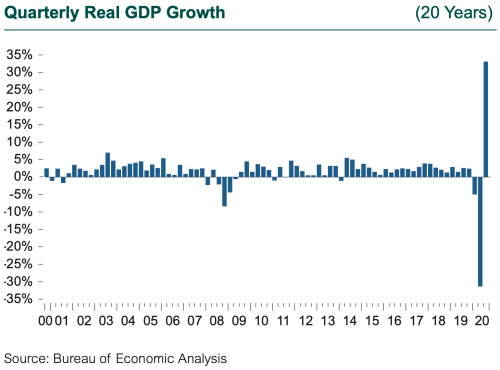

GDP growth came roaring back in 3Q20 as expected, notching a 33.1% gain, following the 31.4% decline in 2Q. The 3Q growth rate set a record by a wide margin (as did the decline), but the interpretation of quarterly GDP growth is problematic when trying to understand the true condition of the U.S. and global economies. GDP is customarily reported as quarterly growth, translated to an annual rate, which helps remove some of the seasonal noise that interferes with evaluating economic activity in normal times. The past nine months have been anything but normal, and annualized quarterly growth rates on either side of a global economic shutdown are perhaps less meaningful than analyzing the level of current and future economic activity relative to that seen before the onset of the pandemic. The huge jump in 3Q still leaves GDP 3.5% below its previous peak (4Q19). Employment remains more than 10 million jobs short of the level reached in the U.S. in February of this year, and many other measures of economic activity such as personal consumption remain below pre-pandemic levels.

The surge in 3Q GDP clearly reflects the gradual reopening of the U.S. and global economies that began back in May. The sharp increases in jobs, spending, and output were concentrated in May, June, and July. Growth in subsequent months has been much more modest. High-frequency tracking of the economy from the likes of GDPNow (from the Federal Reserve) and IHS Markit not only signaled slowing growth in August and September, but these forecasters are now expecting 4Q GDP growth to cycle back down to 5% annualized.

This would bring the level of GDP back close to where we started 2020, but the road forward into 2021 will be challenging. Growth across industry sectors, regions within the U.S., and occupations and income groups has been widely disparate. Technology illustrates the dichotomy. Defined as a combination of the Information Technology and Communication Services sectors, technology has seen lights-out performance in the stock market, up 22% collectively year-to-date through September, and accounts for 39% of the market cap of the S&P 500. Yet these two sectors account for just 6% of GDP, and only 2% of the U.S. job market as of August. The vast majority of jobs lost during the pandemic were in services (transportation, health care, financial business, and personal) as well as hospitality and retail. These sectors are underrepresented in the stock market, yet they employed a substantial portion of the U.S. workforce as the pandemic struck.

The slowdown in August, September, and into the fourth quarter came in part from a concern by both businesses and consumers about the end to the stimulus payments and to extended unemployment benefits in September. Without another round of stimulus and further extension of jobless aid, growth will likely be restrained as the economy continues to operate under pandemic constraints and the effect from the stimulus earlier in the year wanes. The increase in COVID-19 infection rates both around the U.S. and the world, the so-called third wave, will further burden strained medical systems and increase pandemic-related deaths. The rising tide of infections may force the return of more stringent restrictions at the state level to control the virus, although a sudden stop to economic activity similar to what happened in the spring is unlikely.

Not all the economic news is dour as we head into the fourth quarter. Manufacturers’ orders for durable goods have shown considerable strength, and consumer purchases of durable goods have been incredibly robust. Excluding capital goods like defense hardware and civilian aircraft, orders for durable goods have fully recovered to pre-pandemic levels. Trade has surprised on the upside with a narrowing of the trade deficit, even with demand for exports depressed by weakness in the global economy. Another surprising source of strength has been the housing market. Investment in new housing has already reached its pre-pandemic peak, driven by low mortgage rates and newly created demand for improved and larger housing by people leaving the urban cores of many large cities. Underlying demographics such as the aging baby boom and the maturation of families in the next generation suggest this trend is near-term in nature and will likely fade as we see some sort of resolution to the pandemic, perhaps in the second half of 2021.

Government assistance targeted to aid those affected by pandemic-related closures helped greatly to support household incomes, spending, and therefore production. While the job market has a long way to go to recover all the jobs lost, the unemployment rate has surprised to the positive, falling from 14.7% in April to 7.9% in September. The thorn in the job market’s side has been the number of initial unemployment claims, which remains stubbornly high at 837,000 in September, still far above prior periods of stress. For reference, at the bottom of the GFC in March 2009, initial claims hit 665,000.