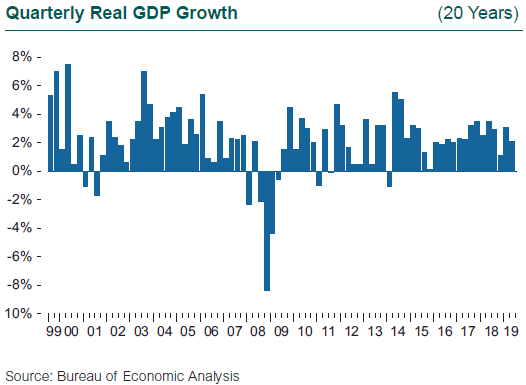

The U.S. economy continued its now-record expansion in the second quarter with a 2.1% gain in GDP, slower than the robust 3.1% in the first quarter but well ahead of expectations. Consumer spending rose 4.3% in the quarter, supported by solid gains in the job market and disposable income growth of 5% in each of the first two quarters of 2019. Offsetting the gains in consumption were hits to GDP from exports, non-residential business investment, residential investment, and a drawdown in inventories. The economic news for the U.S. during the quarter was largely good, and better than the headlines would lead us to believe. Yet the Fed proceeded with a widely anticipated (and clearly signaled) interest rate cut in July, lowering the Federal Funds rate target by 25 basis points.

How did we get to a situation where the expansion continues but the Fed acts to cut rates? In classic Fed-speak, the announced reasoning is “a mid-cycle adjustment to policy.” To be fair, while the job market and overall GDP data are coming in solid for the U.S., the global economy is clearly showing signs of slowing, and the uncertainty stemming from trade tensions is top of mind. Chairman Jerome Powell noted three reasons for the rate cut: (1) to insure against downside risks from slowing global growth and trade tensions; (2) to mitigate the effects those factors are already having on the U.S. outlook, even if they haven’t shown up in the data; and (3) to enable a faster return to the Federal Reserve’s symmetric 2% inflation target.

It is important to note that the Fed made clear this July rate cut is not likely to be the first in a series. After initial confusion, the markets simply interpreted this Fed comment as fewer rate cuts this year than were previously priced into bond yields.

Key to the Fed’s perceived latitude to lower rates is the persistent surprise of low inflation. After breaking through the Fed’s 2% target in 2018, inflation has once again subsided. Headline CPI rose 1.6% in June (year-over-year), dragged down by a 3.4% decline in energy costs. In fact, core CPI (less food and energy) rose 2.1% over the past 12 months, pushed up by the rising cost of shelter, apparel, and used vehicles. While annual wage gains have moved above 3% for the first time since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), wage pressures have yet to show up in headline inflation. The impact of tariffs on consumer prices has not affected the broad CPI data, as the tariffs to date have been narrowly targeted.

Foreshadowing the expected slowdown in the U.S. economy is the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), a forward-looking measure of business expectations for manufacturing demand and production. The mid-year 2019 reading of the PMI hit 50.6, very close to the line dividing expansion from contraction (50), and the lowest reading since 2009. Producers cite the twin worries of slowing global growth and trade tensions; the 5% drop in exports and the softening of business spending in the second quarter data certainly support these concerns. Other concerns about a material slowdown to GDP growth include the waning impact on domestic spending that has come from rising stock prices and fiscal stimulus since the GFC. Further concerns include the effects of potential new tariffs, and the slowdown in inventory accumulation. The U.S. economy is also approaching capacity constraints as the expansion reaches into record territory. Unemployment has hit a generational low of 3.6%; at some point firms’ difficulties in finding new and replacement staff will weigh on overall workforce growth.

The nine interest rate hikes enacted by the Fed through 2018 raised the cost of borrowing for both businesses and consumers, and while the reversal of Fed policy since January halted the trajectory of rates, the impact of the increases since 2016 is still working its way through the economy. Higher mortgage rates slowed housing markets, pulling existing home sales down by more than 10% over the course of 2018. Rates for 30-year mortgages have fallen by more than 110 bps since November 2018, and home sales have bounced back since the start of the year, but the recovery has been uneven, concentrated in the South and the West. Investment in new homes, as measured by permits, began slipping in 2018 and is still down more than 10% (year over year) through June. New residential construction, restricted in many locations by supply and cost factors, has lagged the pace set in typical expansions since the GFC.