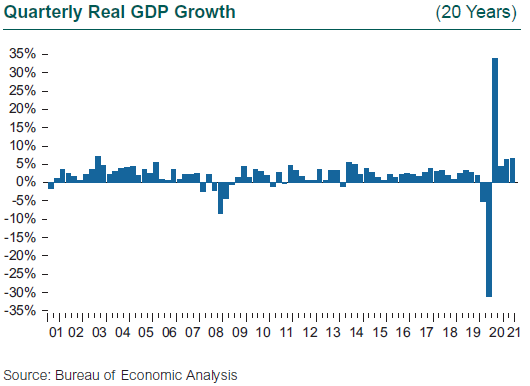

GDP grew at a 6.5% annual rate in 2Q21 and regained the level last seen in February 2020, before the COVID pandemic spurred a global shutdown in economic activity. Our focus during the pandemic has been on the level of economic indicators—GDP, employment, unemployment, consumer spending, imports and exports, and personal income. Traditional measures such as annualized GDP growth lost meaning around the plunge and sharp recovery that defined the shutdown and reopening experience. Reaching the previous level of real GDP is a major milestone; now, GDP growth will regain some meaning as a way to track economic progress. Other key indicators like employment have yet to regain their pre-pandemic levels. In fact, employment has been the measure that took the greatest hit and has the furthest to go before claiming full recovery. We lost over 22 million jobs in the U.S. in March and April of 2020; while we have gained 15.5 million back, that’s still almost 7 million short. The lost jobs were spread across many industries, but the deepest losses and the greatest deficits left to recover are in lower-paid sectors with concentrations of hourly jobs, including hospitality and travel-related industries.

The gains in GDP in 1Q and 2Q were startling and robust, yet still a bit less than economists expected. The Federal Reserve issued a forecast of 7% growth for the year in June 2021, but the 1Q figure was revised down to 6.3%. Growth in 3Q is expected to be stronger than 2Q, but consensus expectations for the year are coming down from 7%. Restocking depleted inventories was expected to be the main driver of growth this year, along with incredibly robust spending by consumers, but supply bottlenecks led to an actual decline in private inventory investment in 2Q, particularly in retail goods. Economists now estimate that in the second half of the year, inventory building is expected to account for as much as two-thirds of GDP growth.

Supply bottlenecks are really the story of the year for many markets in the global economy, both in goods such as building materials, commodities, and auto parts (such as vital computer chips), and in labor for a number of industries, in particular those originally hit hardest like hotels, restaurants, retail, and travel. The stories told by businesses unable to fill multiple open positions contrast sharply with the 7 million job deficit. So what gives? Fueling personal consumption demand has been a singular economic period where the steepest recession in terms of job losses and GDP decline in 70 years was accompanied by NO decline in total personal income. In a normal downturn, as individuals lose jobs and companies close their doors, spending sags as consumers and companies cut back. Unprecedented policy actions to support both individuals and businesses kept incomes in aggregate from falling at all, yet shutdowns held back supply in the face of almost no decrease in demand, at least for goods like building supplies, technology, communications, and computer services.

These kinks in supply have led to a spike in headline inflation: the year-over-year Consumer Price Index came in at 5.4% in June, while the much-more-volatile Producer Price Index shot up 19.5% compared to June 2020. After complete or partial shutdowns around the globe, many industries cannot simply restart production and build supply to meet surging demand instantaneously. Producer prices had been tumbling for more than a year prior to the pandemic, and then suffered another shock with the almost-forgotten plunge in energy prices in 1Q20 as Saudi oil producers entered into a price war to establish global energy supply discipline. The price of building materials, specifically timber, became the metaphor for inflation fears, reaching the point of commentary by none other than the chairman of the Federal Reserve. As incomes were maintained and interest in home renovation soared during the pandemic, demand for lumber surged while product from lumber mills was constrained first by total shutdowns and then production processes limited by social distancing protocols. Timber prices shot up over 300% by the start of June 2021, reaching an all-time high of $1,515 per thousand board feet. As production caught up and demand finally eased, prices have since fallen by over $1,000 and are back at 2018 levels (but still up 200% from spring 2020). Such volatility may be extreme, but timber really may be the appropriate metaphor for transitory price increases that will work through many industries and labor markets in the U.S. and global economies throughout 2021 and into 2022.