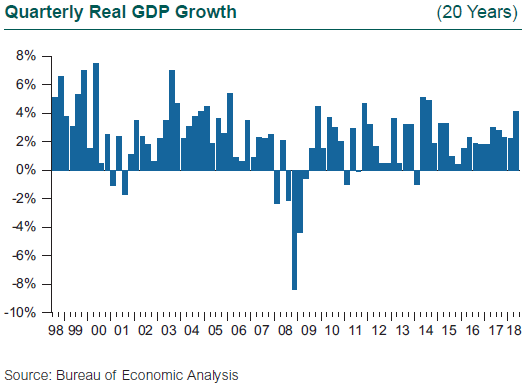

Real GDP growth in the U.S. hit 4.1% in the second quarter of 2018, the strongest quarterly gain since 2014. Many indicators corroborate the story of a thriving American economy: low unemployment, robust consumer spending, elevated business and consumer confidence, and growth in non-residential investment.

However, a big contributor to growth was a surge in exports, likely due to stockpiling ahead of tariffs imposed at the end of the quarter, which may not be sustained for long. Global growth is de-synchronizing, with signs of deceleration emerging in Europe, Japan, and China. Oil prices have rebounded from the lows of 2014, and inflationary pressures such as wages are gradually building.

The Fed raised interest rates for the second time this year in June, and it is telegraphing two more hikes before the end of 2018 and perhaps three in 2019. While the tax cuts at the end of 2017 (a form of stimulative spending by the federal government) are buoying consumer spending, we may be reaching a peak in the current cycle.

Expansions do not die of “old age”; elapsed time is not an economic variable. In addition, the current expansion has seen one of the slowest rates of GDP growth, an average of just 2.2%, compared to a typical expansion average of 3% or greater. That said, the current expansion is one of the longest on record, and it is the imbalances that can develop during long expansions that ultimately lead to a correction. Diverging global growth, and the resetting of monetary policy in the U.S. to return to “normal” ahead of plans by other countries’ central banks, means higher interest rates in the economy with the strongest growth and upward pressure on the U.S. dollar. A more expensive dollar will make U.S. exports more costly, at a time of increased trade uncertainty following the imposition of tariffs. Higher interest rates mean higher borrowing costs, after a decade of cheap debt for those who could get it. The tight labor market poses another source of imbalance, with unemployment dipping to a generational low of 3.8% in May, employers facing challenges hiring talent, and wage pressures gradually building.

The second quarter was clearly another high point for the U.S. economy in the long rebound since 2009. U.S. exports surged 9.3% in the quarter, accounting for a fourth of total GDP growth. With growth weakening in American trading partners, the increase in exports to them does not likely represent a surge in demand but a shift in timing, which will show up in subsequent quarters. The tax cut represents a potentially large fiscal stimulus, and consumers have certainly responded, driving consumption spending up 4% during the quarter and accounting for two-thirds of GDP growth.

Business investment of the tax cut is mixed; equipment spending grew more slowly in the first half of the year compared to 2017, while investment in structures surged at an annual rate of more than 13% in each of the first two quarters.

One surprise in the quarter was a drop in inventory investment, which actually subtracted 1 percentage point from GDP. The upshot is that GDP growth could have been as high as 5%, and the economy now has greater capacity to rebuild inventory, suggesting a boost to future growth.

Another surprise in the GDP report was a drop in residential investment. The housing market has been a bit of a riddle as this long recovery has unfolded. The inventory of existing single-family homes reached its lowest reading on record for the month of May (1.65 million). Inventory levels keep dropping, reaching a supply of 4.1 months in June while a 6-month supply is considered normal.

Yet home prices are high and rising everywhere. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) reported that home price indices rose year-over-year in the first quarter in all 50 states and in each of the 100 largest metro areas. The number of homes worth less than their mortgage has dropped by 80% since 2011, which should lead to an increase in potential inventory. Three factors have weighed on the inventory of homes for sale. A substantial number of single-family homes were converted to rental units starting in 2006. Second, Americans don’t move as much; mobility in 2017 dropped to a post-World War II low. Third, starts have been hindered for 10 years on the supply side, with high timber and construction costs, a shortage of building sites, and restricted access to credit. Demand may be there, but builders have been unable to put up enough homes.