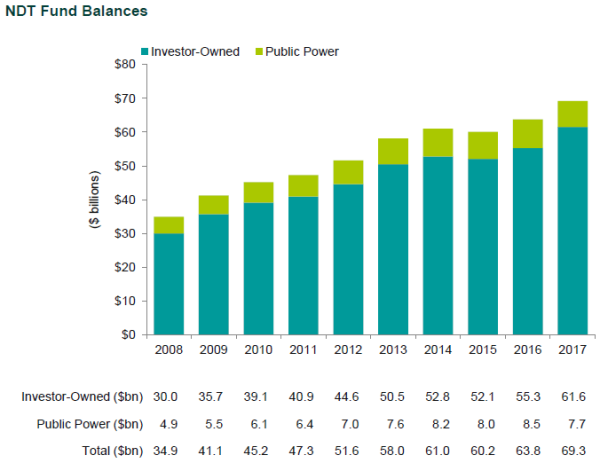

Callan’s annual Nuclear Decommissioning Funding Study offers insights into nuclear decommissioning funding in the U.S. Our key findings show the health of nuclear decommissioning funding improved in 2017 as the funding level reached 78%, up from 70% in 2016. Other highlights from the study:

- Nuclear decommissioning trust (NDT) funding rose 8.7% to nearly $70 billion largely due to strong capital market performance

- Decommissioning costs totaled approximately $89 billion in 2017, up 161% over their 2008 level

- Total contributions were $562 million in 2008 but are now under $300 million

The study covers 27 investor-owned and 26 public power utilities with an ownership interest in the 99 operating nuclear reactors and 10 of the non-operating reactors in the U.S. The number of operating nuclear power reactors in the U.S. has declined by just one since we first conducted our study five years ago.

While the nuclear energy industry looks relatively healthy on the surface, a number of issues are threatening the viability of nuclear power as a source of reliable and relatively clean energy in the U.S.

Today nuclear energy generates 20% of the nation’s electricity, but the fleet is aging. Of the 99 operating reactors, 86 have already received their 20-year license extensions. Of the operating reactors, 59 have licenses that expire sometime in the next two decades, though 12 have or can apply for a 20-year license renewal. Add to that the intention by several owners to shut down some of units prematurely, and nuclear energy as a continuing source of meaningful electricity generation in the U.S. is in question.

A Brief History

After the Three Mile Island incident in 1979, U.S. nuclear power expansion ground to a halt. As memories of the incident faded—and amid an expected rapid rise in energy demand in the coming decades—the nuclear power industry began to re-emerge with the backing of the federal government. As a result, utility owners started to apply for permission to build new reactors.

But delays, cost overruns, the Fukushima nuclear power disaster, the Global Financial Crisis, and a flood of cheap natural gas put most of those plans on hold. Two reactors closed in recent years (Vermont Yankee in 2014 and Fort Calhoun in 2016), while Watts Bar 2 in Tennessee opened in 2016. This reactor became the first nuclear reactor to come online in the U.S. since Watts Bar 1 in 1996. Only one project in Georgia is still being built.

Add to that increased output from renewable energy, the still-unresolved issue of a national repository for spent nuclear fuel, millions of dollars in upgrades required after Fukushima, the risk of rising seas and potentially catastrophic storm surges, and owners finding many new and existing plants are no longer economically or politically viable.

Global Interest in Nuclear Power

While the future of nuclear power in the U.S. may be in question, there is a significant push toward nuclear power in many areas of the world. According to the International Atomic Energy Agency, as of October 2018 there were 53 reactors under construction outside the U.S., including 12 in China, 7 in India, 6 in Russia, 5 in South Korea, and 4 in the United Arab Emirates.

The global nuclear industry is also working to develop highly advanced reactors based on new technologies that should improve safety and economics. One such advancement is small modular reactors (SMRs). SMRs have many useful applications, including the ability to generate emission-free electricity in remote locations where there is little to no access to the power grid. They can be factory-built and delivered and installed at the site in modules, hence their name.

In addition, some SMRs will have long operating cycles between refuelings and others can be air-cooled, making them a good fit for arid regions. A more advanced set of nuclear technologies is also being developed that includes molten salt reactors, liquid-metal-cooled reactors, and high-temperature gas reactors.

While building a nuclear power plant today is costly and time-consuming, once it is up and running it produces reliable and relatively cheap electricity without generating greenhouse gas emissions. The industry’s hope is that the new, highly advanced reactors will be safer, cheaper, and more efficient, and that nuclear power will remain a meaningful source of electricity.

In the meantime, nuclear decommissioning funding for existing plants in the U.S. remains healthy, indicating that the industry has been responsible in ensuring that the funds are there to cover decommissioning costs.

See our 2017 study for comparison.

$70B

Value of nuclear decommissioning trust (NDT) funding in 2017