The Federal Reserve has two very public mandates: to support employment growth and to maintain low, stable inflation. When the economy falls into recession (GDP and jobs are contracting) and unemployment rises, the Fed typically steps in and lowers interest rates. Lower rates stimulate borrowing by consumers and businesses, and thereby spur demand that will ultimately pull the economy back into the black with positive economic growth and a resumption of hiring. When inflation rises, the Fed typically steps in and raises interest rates. Higher rates slow borrowing by consumers and businesses, and thereby lessen demand and slow the upward pressure on prices.

There is a balancing act on both sides of this policy equation: How much stimulus is enough to get the economy growing and spur recovery in the job market to pull down unemployment, before the resumption in demand pushes up prices? How high can interest rates go before the economy slows enough to tip into recession and unemployment shoots up? While this characterization is incredibly simplistic compared to the complex inner workings of the Fed, and ignores for the moment the impact of the Fed balance sheet and monetary tightening or easing, the story works to help explain the conundrum we currently face as we move into the rest of 2023.

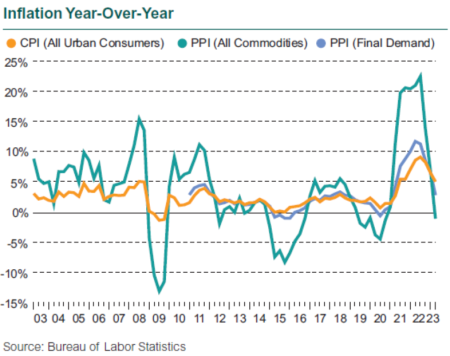

The last three years saw incredible mayhem in the supply chains, capital flows, and job markets of the world, with equally volatile yet weirdly out-of-sync (at times) mayhem in the capital markets. We suffered through a pandemic with an uneven global policy response, and the invasion of Ukraine in winter 2022. Global energy fell to an effective price of zero in 2020 only to skyrocket immediately thereafter. Inflation surged hard after more than a decade of suppression, and central bank responses to withdraw stimulus and put out the inflation fire in 2022 spooked equity markets and drove fixed income returns to their worst year ever.

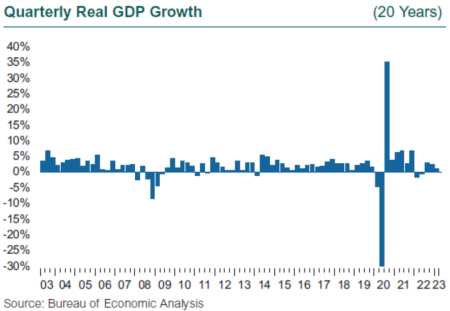

Underneath all this, the U.S. economy has actually held up pretty darn well. We regained the pre-pandemic levels of GDP and employment in fairly short order, given the depth of the declines. The job market in the U.S. has been particularly robust; even in 2022 as the capital markets plummeted, we added 4.8 million jobs during the year, with two monster months in February and July, and an average of 330,000 new jobs in the other 10 months of 2022. On the downside, overall gains in jobs hide the continued mismatch between the supply of jobs from employers and the type of jobs workers are demanding. Many trade and service industries remain woefully understaffed. Personal income surged, first through pandemic support in 2020 and the inability to spend in lockdown, and then as wages and salaries rose when economic growth burst into the open in 2021 and 2022. However, inflation ate into income gains and drove up prices for businesses, crimping real returns and company margins. Now that the Fed Funds rate has reached 5% and mortgage rates are at 7%, is it time for us to tip into recession? Did the Fed do “too much, too late?”

Trends in the 1Q23 Economy

1Q23 GDP grew 1.1%, a definite slowdown from the second half of 2022, and below consensus expectations of 2%. Two culprits for the slower growth were weaker retail sales and a drop in new home construction. Another culprit was inventory reduction—companies worked down their stockpiles. Reducing inventories in anticipation of slower demand can be a self-fulfilling prophecy, as inventory reduction is a negative to GDP, but it can also set the economy up for a stronger 2Q, with the potential to rebuild inventory in the coming months. The consensus among economic forecasters is for substantial slowdown in 2023, to near zero growth in 2Q and 3Q, reaching the soft landing that is the holy grail of central banks.

Over history, however, we have not enjoyed soft landings in recessions; unemployment has spiked far beyond what would be thought of as a soft landing. The data for tracking recessions are all lagged, but the sequence of events in the economy is typically 1) slowing activity that takes a while to show up in the GDP data, then 2) cutting back in the form of spending and hiring, 3) layoffs starting in high-flying industries, leading to 4) the multiplier effects of the slowdown snowballing into significant job losses across the broad economy. The stock market usually prices in recession first, often far ahead of the economic data, and then the market begins to advance, pricing in the recovery while the recession is still unfolding.

The bond market has been signaling belief in recession with an inverted yield curve. The market fully believed in the Fed’s interest rate plans in March 2022 when inflation took off, and the yield curve shifted up sharply. As the year went on, the bond market then began worrying that the Fed would have to reverse course “soon” and start cutting rates to stave off recession, hence the inversion of the yield curve. The Fed has made it clear that inflation remains concern No. 1, and the potential to cause a recession has not entered its deliberations. The strong job market in 1Q—almost a million new jobs—gives the Fed cover to continue course. The storm clouds on the horizon are the various measures of inflation: CPI-U and PCE both rose 5% in the first quarter, and the employment cost index for private industry rose 4.8%. While these rates are high relative to longer term history, they are down substantially from the peaks of mid-2022.

So higher interest rates are working, slowing demand and lessening price pressure, but inflation has a habit of being sticky on the downside. Squeezed margins means pressure to trim costs (and raise prices if possible). Highly visible layoffs in technology may soon expand to the broader economy. The chance of a recession in 2023 remains high.

Disclosures

The Callan Institute (the “Institute”) is, and will be, the sole owner and copyright holder of all material prepared or developed by the Institute. No party has the right to reproduce, revise, resell, disseminate externally, disseminate to any affiliate firms, or post on internal websites any part of any material prepared or developed by the Institute, without the Institute’s permission. Institute clients only have the right to utilize such material internally in their business.