Capital markets abhor uncertainty, and there is no greater human-generated uncertainty than war. The Russian invasion of Ukraine upended expectations for an orderly slowdown in economic growth from the surge in 2021, and for the spike in inflation to subside as pandemic-induced supply chain bottlenecks cleared.

Amid this geopolitical upheaval and humanitarian catastrophe, the equity and fixed income markets were both down in 1Q22. How often does that happen? More than we expected. Looking at data back to 1926, there have been 37 quarters in which returns on stocks and bonds were both negative, almost 10% of all quarters over that period. Before now, the most recent quarter was 1Q18, and before that, the 2nd and 3rd quarters of 2008, as the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) began unfolding. In case you were wondering, the S&P 500 plunged 19.6% in 1Q20, while the Bloomberg Aggregate rose 3.1%. The frequency of down quarters for both stocks and bonds has been much lower since 1990 than in the first 60 years of the data set.

Looking at annual returns, there have been only two calendar years when stocks and bonds were both down, 1931 and 1969 (with a near-miss in 2018). The point: Over more recent history, stocks and bonds down together is relatively unusual.

1Q22 Trends in the Economy

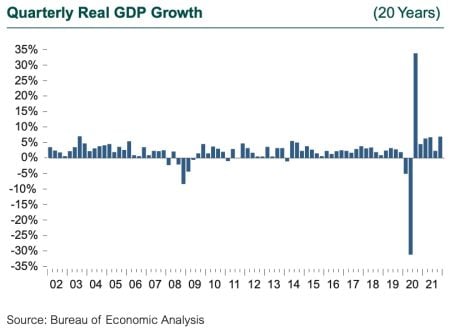

The war also hit business and consumer confidence, and the 1Q GDP report surprised all with a 1.4% drop, following a 6.9% surge in 4Q21. The 8.3% swing in growth came from a huge drop in inventory investment and net exports. Imports surged 17.7% while exports declined 5.9%, a sharp reversal from 22.4% growth in 4Q21. The drop in GDP is a surprise because the economy is otherwise healthy, with a strong job market. Final sales to the private sector grew 3.7% in 1Q, up from 2.6% in 4Q21, suggesting strength in aggregate demand.

The concern going forward is that the confidence to spend and invest will be tested by rising interest rates, skyrocketing inflation, war uncertainty, and the prospect of a recession.

The Fed raised rates at its March meeting, bringing the Fed Funds rate up to 0.25%-0.50%. The median projection by FOMC members for the Fed Funds rate was 1.90% at the end of 2022, rising to 2.80% in 2023. However, the range of projections (1.4% to 3.2% by year-end) from Committee members reflected a high degree of uncertainty. As of quarter-end, the market was anticipating nine hikes in 2022, three more than expected by the Fed.

The war in Ukraine and the sanctions imposed on Russia are now piling on to supply bottlenecks, with particular concerns about food and energy supplies, and putting into question the assumption that inflation would ease later in 2022 and into 2023. CPI-U for the U.S. hit 8.5% for the 12 months ending in March, the highest rate since the period ending December 1981. Driving the increase were prices for gasoline, shelter, and food. The energy index rose 32%, with gasoline prices up 48% year over year. The food price index rose 8.8%, and like the broad CPI, it was the biggest surge since 1981.

Russia and Ukraine are vital suppliers to regional and global food supplies. In addition to price inflation, the war has raised serious concerns about the 2022 spring planting and harvest later in the year, and the potential for disaster in food-insecure parts of the globe.

The impact of the war is most direct and dramatic in eastern Europe and central Asia (EECA). The economic ties with Russia and Ukraine are extensive for many countries in the EECA bloc. Russia is the largest market for some countries, and the largest source of goods and energy for others. Tourism and foreign direct investment from Russia is substantial, and salary remittances from foreign workers in Russia are a vital source of income for many EECA countries. Poland attracted a substantial number of Ukrainian workers.

Even without close ties, countries within the EECA, western Europe, Africa, and the Americas are vulnerable to disruptions in the flow of goods, services, and energy stemming from the conflict.

If recession is often identified by consecutive quarterly declines in GDP, why wouldn’t the 1Q22 decline signal a potential downturn? First, aggregate demand remains robust. Second, household balance sheets are healthy. A labor market characterized by high employer demand, low unemployment (3.6% and falling), and rising compensation suggests continuing growth in consumer spending. Business investment will respond to this strong consumer demand. High frequency data show resilient growth in spending on travel and entertainment, and a recovery from the sharp drop in activity during the Omicron wave.

While expectations for economic growth in the U.S. are clearly lower since the Russian invasion, with GDP projections for 2022 down from 4% to 3% or lower, they are still positive. The impact of the war may be more consequential for Europe, with its greater dependence on energy imports. Risk of recession is higher, but not yet the expected case for 2022.