Listen to This Blog Post

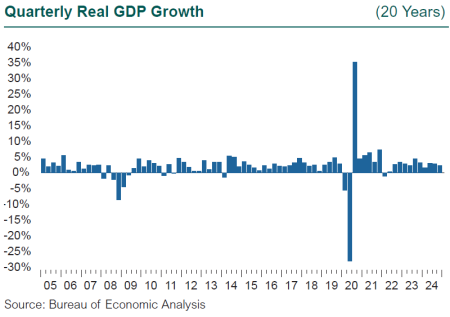

Economists and market prognosticators were all so sure that a recession was in the cards, if not in 2023, then surely in 2024. But one never came, and now we are left scratching our collective heads as to what is in store for the global economy. The U.S. economy showed a few signs of slowing during 2024, scattered across indicators like inventories and consumer debt levels, especially for autos, and exports and imports. But in the end solid GDP growth persisted, and the job market proved resilient despite some head fakes during the year. The hurricanes in the Southeast took a bite out of consumer optimism and the job market in the fall, when new jobs fell precipitously in October to recessionary readings (below 50,000). But hiring came bouncing back in November and December, and the U.S. economy clocked consecutive months with greater than 200,000 new jobs, a level associated with continued economic expansion. The unemployment rate remains low at 4.1%. GDP grew 2.5% over the course of 2025, after a gain of 2.9% the previous year.

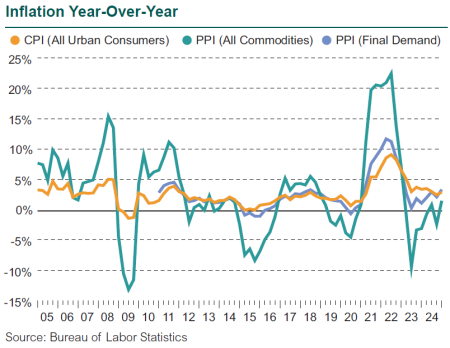

The Federal Reserve’s process of rate hikes to tackle elevated inflation, in which the Fed Funds rate and mortgage rates and credit card and auto loan rates all rose dramatically within a very concentrated period of about six quarters, barely dented the U.S. economic growth engine. A tumultuous federal election year and spreading geopolitical turmoil around the globe has not hurt consumer confidence much. We can trace the consumer optimism in broad strokes to the strong, steady job market, and wages and salaries that have risen fast enough to finally outpace inflation, a reversal that took hold when the rate of inflation dropped sharply from its peak in 2022. Real average hourly earnings increased 1% over the course of 2024 (in other words, nominal wages outpaced inflation by 1%). Real wage growth has sustained confidence and boosted disposable income and spending.

The Fed signaled that it completed its mission to raise interest rates to fight inflation in mid-2024 and began cutting rates in September 2024. The Fed cut a total of 1% in 2024, and the current target range for the Fed Funds rate is 4.25%–4.50%. Longer term, the midpoint of the Fed’s target for short rates is 3.0%, but the size of the range around this midpoint is unprecedented, 2.4% to 4%, suggesting a wide range of opinions at the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The debt market is pricing in a halt to the Fed’s rate cuts at 4%, suggesting belief that inflation and therefore short rates may have to settle in at levels higher than previously thought.

Despite the gains in real wages, the shadow of inflation still looms. The effects of this once-in-a-generation inflation spike will hang over companies and consumers for years. Inflation is a rate of increase in general prices; even if we hit the Federal Reserve’s articulated goal of 2% long term, it still means prices continue to rise, every year. More importantly, that 9% spike in inflation is now baked in: Prices are “permanently” higher, and they are continuing to rise, just at a lower rate. Simple daily indicators abound that remind households and companies and governments that everything is substantially more expensive. None are more prevalent than the cost of food, both at home and at restaurants: How much did I just pay for those eggs?

Strong GDP growth suggests little easing in tight labor markets; the prospect for continued inflationary pressure from the labor market is high. Getting inflation down to the Fed’s stated goal of 2% will take time and some discomfort. Squeezing out the last of excess inflation will require a period of below trend growth, a loosening of the labor market, and the pain of a rise in unemployment. In the face of this labor market tightness, deporting undocumented workers has the potential, most mainstream economists agree, to greatly restrict the supply of labor in agriculture across the country and could result in substantial upward pressure on the cost of food either from reduced supply (more likely) or increased wages to lure American workers to do these jobs (less likely). Other sectors including construction and services could see similar severe tightening in their supply of labor and upward pressure on prices.

The other part of the inflation shadow is the prospect of trade wars, namely the imposition of tariffs by the U.S., with potential retaliation from its trading partners. Within the complex web of global sourcing, assembly, and delivery of goods and services by U.S. companies, it is not clear what or who will be subject to a tariff. American automakers source parts, including computer chips, and assemble vehicles outside of the U.S. American tech companies make much of their hardware either entirely overseas or with components from overseas. Auto companies from Germany and Japan assemble autos in the U.S. How do we define an import car, exactly? Tariffs raise the prices to the end buyer, leading to more inflationary pressures. Spiraling prices may be the catalyst of the long-awaited recession, finally killing growth in the current economic cycle.

Disclosures

The Callan Institute (the “Institute”) is, and will be, the sole owner and copyright holder of all material prepared or developed by the Institute. No party has the right to reproduce, revise, resell, disseminate externally, disseminate to any affiliate firms, or post on internal websites any part of any material prepared or developed by the Institute, without the Institute’s permission. Institute clients only have the right to utilize such material internally in their business.